Scalper1 News

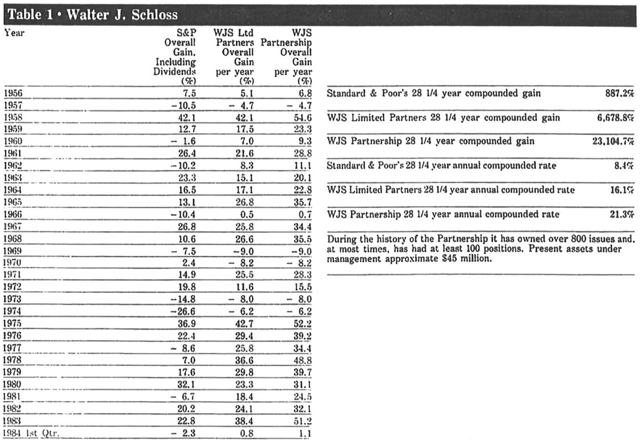

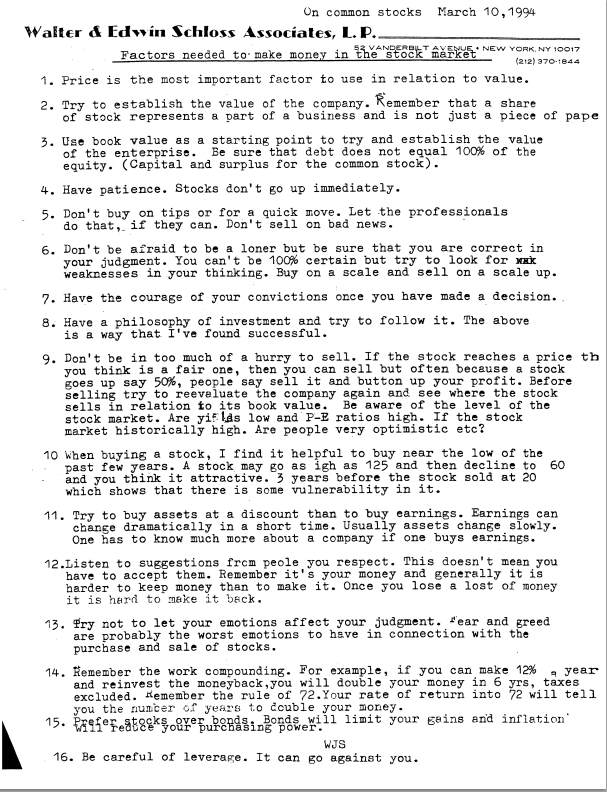

Summary Walter Schloss was one of the best investors of all time. While firmly intrenched in Graham’s net-net strategy, an absence of opportunities caused him to change course. No matter whether you choose Schloss 1.0 or Schloss 2.0, his style is really easy to apply. Basically we like to buy stocks which we feel are under-valued, and then we have to have the guts to buy more when they go down. And that’s really the history of Ben Graham. That’s it.” Who do you look up to when it comes to investing? A lot of investors put their faith in Warren Buffett – and for good reason. Buffett has one of the best investment records in the industry, and has been racking up great returns for investors since the early 60s. Lesser known, but no less impressive, however, is a man that Buffett warmly refers to as “Big Walt.” When it comes to investing, Walter Schloss is a legend. Warren and Walter met at a Marshell Wells shareholder meeting, while the company traded below net current asset value, and ended up sharing an office at Benjamin Graham’s investment firm in the 1950s. Graham’s original net-net strategy has produced fantastic returns since at least the 1930s. At the time, Graham charged both with finding net-net stocks and both ended up adopting that same strategy in their own private practices years later. While Buffett eventually moved on to buying large well-protected firms in the 1970s, Walter Schloss was able to earn one of the most enviable records on Wall Street by sticking to Graham’s original framework. As Buffett put it in Superinvestors of Graham-and-Dodsville, “…He knows how to identify securities that sell at considerably less than their value to a private owner… He simply says, if a business is worth a dollar and I can buy it for 40 cents, something good may happen to me. And he does it over and over and over again. He owns many more stocks than I do – and is far less interested in the underlying nature of the business; I don’t seem to have very much influence on Walter. That’s one of his strengths; no one has much influence on him.” Schloss’ record hasn’t exactly disappointed. Over the 47 years since the closure of Graham-Newman, the high school only graduate managed to earn a solid compound annual return of 16% for his investors after management fees. While that’s an incredible 60% higher than the S&P 500, his actual portfolio returns were much better. Just how good? When Warren Buffett dubbed Schloss a super investor back in 1984, Walter had already been managing money for 28 years. According to records obtained by Buffett, Walter Schloss’ returns before management fees stood at a compound annual return of 21.3%. Not bad for a guy who never attended college! (click to enlarge) Many investors think that making money on stocks requires using advanced investment strategies, or having a 6th sense about the market, but Walter’s investment strategy was surprisingly simple. In fact, it’s so simple and so profitable that small retail investors should really pay attention. Walter Schloss on What Not to Do Many investors love to forecast the direction of the markets, but while it’s possible to guess correctly from time to time, investors have proven unable to make accurate market predictions to the extent that they just can’t be relied on to yield great returns over the long run. Walter Schloss understood this well, so stayed clear of this trap. In an article titled Setting the Right Pace , he clarified that his stance wasn’t just philosophical but stemmed from his inability to know which way the market will go, “I am not good at market timing, so when people ask me what I think the market is doing, their guess is as good as mine.” It wasn’t just market timing – Schloss also distrusted the promises of management and earnings projections. When talking about his investment in the Milwaukee Rail Road, a firm that Schloss was told would be acquired, Walter Schloss recounted, “I paid $50 a share for it because I was going to get $80. Well, that was in 1969, the market went down and the deal didn’t go through. You have to be very careful when people say they are going to do something.” On the earnings front, Discounted Cash Flow calculations applied to equities were strictly out due to the trouble estimating profits to get a solid valuation. As Walter explains, “I really have nothing against earnings, except that in the first place earnings have a way of changing. Second, your earnings projections may be right, but people’s idea of the multiple has changed. So I find it more comfortable and satisfying to look at book value.” In fact, as time passes, earnings become even more tricky to estimate. In a letter reprinted in the Harvard Business Review in 1965, Schloss wrote, “…earnings are much more likely to fluctuate than are book values, and therefore, estimating longer term earnings than, say, the next year or so can be subject to serious error.” But it wasn’t the case for Schloss that all earnings based valuations were out. In Sixty-five Years On Wall Street , he highlights which companies investors can produce plausible profit projections for and which firms they can’t, “…one of the things about these undervalued stocks… is that you really can’t project their earnings. There are stocks where there’s growth and you project what’s going to happen next year or five years. Freddie Mac or one of these big growth companies, you can project what they’re going to do. But when you get into a secondary company, they don’t seem to have that ability.” Interestingly, while most professional money managers focus on earnings, Schloss based his investment strategy on something that proved far more valuable in practice. Walter Schloss’ Ideal Investments During his early career, Walter Schloss leveraged Benjamin Graham’s famous net-net stocks strategy. From Setting the Right Pace, “I used the same investment approach I used at Graham-Newman – finding net-net stocks. It was all about capital preservation because I had to serve in the best interests of my investors.” Graham developed his net-net stock strategy after suffering devastating losses in the 1930s. His focus was on finding a strategy that would help protect an investor’s downside while providing significant upside potential. The strategy proved exceptional. While Graham found that he could produce average annual returns in excess of 20% per year by buying a hundred or so decent quality net-nets, he also found net-nets to provide good downside protection. Graham may have underestimated the strategy’s potential, however. Later studies pegged the strategy’s average annual pretax returns at between 20 and 40% . “Back in the 1930s and 1940s there were lots of stocks, like Easy Washing Machine, and Diamond T Motor, that used to sell below working capital value. You used to be able to tell when the market was too high by the fact that the working capital stocks disappeared. But for the last 15 years of so, there haven’t been any working capital companies.” While Walter Schloss and his son, Edwin, hunted for net-net stocks throughout their career, as the markets moved higher, there were far fewer net-nets on offer. To compensate for this dry spell, Schloss shifted to buying distressed firms that were trading at low prices relative to book value. From 65 Years on Wall Street, “[Our strategy has] changed because the market has changed. I can’t buy any working capital stocks anymore so instead of saying well I can’t buy ’em, I’m not going to play the game, you have to decide what you want to do.” Net-net stocks almost completely dry up during overheated markets, which can spell trouble for investors who insist on sticking to domestic securities. But, there’s always a depressed market somewhere, which gives investors willing to venture out into friendly international markets a huge advantage. Currently, Net Net Hunter members are finding the most promising opportunities in Japan . Walter Schloss Investing 2.0 Perhaps mistakenly, Schloss stubbornly stuck to North American markets, forcing him to shift his strategy. Like Buffett in the late 1960s, he just couldn’t rack up the same returns without significantly more work. But, rather than focus on growing businesses, Walter stayed true to his deep value roots with a natural extension of Graham’s net-net stock strategy. While not nearly as profitable, it still produced good returns. From a 1985 Barron’s article, The Right Stuff: Why Walter Schloss Is Such A Great Investor, “[W]e look at book value, which is a little lowering of our standards…” Schloss knew that second editions of a product were not always better. Despite the lack of net-nets, Schloss put Graham’s principles to work by buying firms for less than the value of their realizable asset values. In The Right Stuff , he explained, “You don’t have to just look at book value. You can look at what you think companies are worth, if sold. Even if it isn’t going to be sold. Are you getting a fair shake for your money?” And that’s really what Walter Schloss investing comes down to – buying a dollar for far less than it’s worth. Depending on how you employ this principle, however, understanding the business can be critical to knowing if you’re getting a good deal or not. From The Right Stuff, “I don’t understand high tech. I’m sure there are probably good buys in some of these companies that have been beaten down, but if you really don’t know, it’s better not to get involved.” By contrast, if you maintain a diversified portfolio of net-net stocks, you don’t have to have much understanding of the business at all because you’re taking advantage of the general returns offered by net-nets as a group. Key Criteria For Sleepy Value Investors Not all value investment opportunities are created equally and an investor really has to focus on the best available to yield market-beating returns. Walter Schloss focused on finding net-nets, but moved on to the next best classic value stocks available using simple criteria. In the November 1965 issue of the Harvard Business Review, Walter Schloss mentioned that, “…those companies with large book values in relation to market prices offer the stock holder the greatest rewards…” …highlighting Schloss’ preference for deeply discounted stocks. But this wasn’t the only piece of ranking criteria Schloss looked for. “[B]uy companies that don’t have very much debt, when the stock is selling at a reasonable price in relation to its assets, earnings, and dividends.” As he Highlighted in Walter Schloss: Searching For Value, low debt to equity ratios were a cornerstone of his selection process. Another key consideration were dividends. It’s common for management to think of their own bonuses before the welfare of shareholders, especially as option grants have become more widespread. As a check on mindless self-interest, Schloss also looked for dividends. “I like the idea of company-paid dividends, because I think it makes management a little more aware of stockholders…” With depressed firms, it’s particularly important that management is on the side of shareholders because these firms are often going through major business problems that management has to fix. That doesn’t mean that management has to be gifted, but they do have to have their interests aligned with shareholders. From The Right Stuff, “[T]he Cleveland Worsted fellows did own a lot of the stock, and I guess they felt the thing to do was to liquidate – which they did. Now, that’s unusual. Most companies don’t liquidate. But they were in a poor business. So they did the sensible thing. But companies don’t always do things in your interest, and you have to bear that in mind. Managements, you know, often think of themselves. It depends on the board. One of the things about business is, you try to get in with good people. You don’t have to be smart. They don’t have to be the smartest guys in the world, but you want them to be honest.” In the same article, Schloss described one firm that he thought provided an excellent example, “It’s called Potlatch and it’s a timber company out on the West Coast. It’s not spectacular, but it’s got a lot of timber, and I think the timber’s worth a lot more than the market price of the stock. Now, that’s something you have to look at the figures for see how much money they put back into these plants and so forth. One of the drawbacks to it, from some people’s point of view, is that management owns about 40% of the stock. So, a lot of people say, ‘Oh, I don’t want that; it can’t be taken over.’ But on the other hand, management has an interest in seeing that this company is a success.” He continued, “Now here’s an example of a company that’s not a book value stock, but which I think is a high-class company. It’s the old Corn Products Refining Co., CPC International. I don’t know if you know Skippy peanut butter and Mazola and Mueller’s spaghetti. ……….but those are nice consumer products. Basically, I like consumer stocks. My problem is that you pay too much for them today. They’ve been discovered, so it’s tough. CPC is not the cheapest stock in the world, but it’s got good value. It’s got book value of maybe 27, and it’s got earnings of $4 per share, I’d say. It sells at 40; the dividend is $2.20, so it’s selling at 10 times earnings. Well, you couldn’t start the business today for that. And it’s a nice steady business, not going much of anywhere, but whats the risk on the downside? ………..The stock’s never really taken off, so maybe you’d lose 10% on your money if you didn’t sell it – but that risk seems somewhat limited. Of course, they have problems. They do business in Latin America. But they have good products. So you buy it. Somewhere along the line things work out better for you.” According to Schloss, the upside was limited, but it proved to be a good parking place for his money, “I would use a price of 60 maybe, or 55 [to pegs its value at] – somewhere in that area. But the thing is, it’s a place to park money, too. ……….If this market was very low, I’d say, ‘Well, CPC probably isn’t a great stock to own. If the market is so cheap, you want to get something with a little more zip in it, or potential.’ ” Make High Probability Bets and Diversify In Sixty-Five Years On Wall Street , Schloss was lobbed the question whether he was more of a Buffett qualitative investor, or a Tweedy, Browne quant. His answer showed a lot of humility, “I’m more in the Tweedy Browne side. Warren is brilliant, there’s nobody ever been like him and there never will be anybody like him. But we cannot be like him. You’ve got to satisfy yourself on what you want to do.” He continued, “…the way that’s comfortable for us is to buy stocks where we have limited risk and we buy a lot of stocks. Well, Warren, as somebody said, owning a group of stocks is a defence against ignorance, which I actually think that’s to some extent true because we don’t go around visiting companies all over the country… ” Schloss ran a small investment shop housed in a closet in the offices of Tweedy Browne. Being a small outfit, he didn’t have the resources needed to visit companies and conduct thorough qualitative analysis. Being so small, Schloss preferred buying based on quantifiable metrics. It also never made sense to worry about what the stock would do after he bought it. In Making Money Out of Junk , he explained how deep value stocks set an investor up to capitalize on high probability, statistical, bets, “The thing about buying depressed stocks is that you really have three strings in your bow: 1) earnings will improve and the stocks will go up; 2) someone will come in and buy control of the company; or 3) the company will start buying its own stock and start asking for tenders.” Schloss continued, “The thing about my companies is that they are all depressed, they all have problems and there’s no guarantee that any one will be a winner. But if you buy 15 or 20 of them…” …they’re bound to work out well. “[I]f you buy companies that are depressed because people don’t like them, for various reasons, and things turn a little in your favor, you get a good deal of leverage.” This leverage comes partly from illiquidity and partly from shifting perceptions. Stocks are distressed because people are pessimistic about the company’s future and avoid them. Negative sentiment is often pushed to an extreme, and the stock price collapses. Since buyers avoid the stock, trading volume also dries up. This combination of low volume and a depressed stock price resembles a coiled spring held down by a finger. When something stirs in the firm’s situation which causes investors to reevaluate the company more favourably, buyers rush to purchase shares, demand outstrips supply, and the share price shoots skyward. Getting back to Walter Schloss’ three drivers of price performance, just how frequently do these events occur? In the 1960s, Warren Buffett described net-nets as working out 70-80% of the time within 2 years. Similarly, Schloss thought the odds of success for his deep value stocks were very good. In a 1985 Barron’s article titled, The Right Stuff: Why Walter Schloss Is Such A Great Investor, he explained, “About ever four years we turn over. [F]our years seems to be about the amount of time it takes. Some take longer.” But being selective about your picks is still important. As he mentioned in The Right Stuff: Why Walter Schloss Is Such A Great Investor, “The thing is, we don’t put the same amount of money in each stock. If you like something…, you put a lot of money in it.” Keep Your Head About You When All Others Lose Theirs With a little tongue and cheek, Schloss summed up in Sixty-five Years on Wall Street that the big secret of his and the rest of Buffett’s Superinvestors’ success was that none of them smoked, “I think number one none of us smoked. I think if I had to say it, I think we were all rational. I don’t think we got emotional when things went against us and of course Warren was the extreme example of that.” Psychology plays a huge role in Walter Schloss’ investment success. In fact, if Big Walt didn’t have the degree of emotional intelligence that he has, he would have never have been able to rack up the returns that he did. According to Big Walt, quoted in Walter Schloss: Searching For Value , it starts with perception, “What an investor does to some extent is based on his background. It’s very difficult to tell somebody who is fearful of stocks, ‘Yeah, you should put your money in the stock market.’ if your father lost his money in the Depression, you’ll see things differently.” Later, in the same article, he explained, “I owned some bankrupt bonds in the Pennsylvania Railroad. That would drive most people up the wall – never mind that it worked out beautifully. But people don’t want to buy bankrupt bonds.” As those who are getting free net-net stock picks already know, the same goes for Walter Schloss’ preferred deep value investments, net-net stocks. Since net-nets look scary to many investors, those with a strong emotional temperament have a powerful advantage. “One of our partners said, ‘Walter, I have a lot of money with you. I’m nervous about what you own.’ So I made an exception and said, ‘I’ll tell you a few things that we own.’ I mentioned the bankrupt rail bonds and a couple of other things that we owned. He said, ‘I can’t stand knowing you own those kinds of stocks. I have to withdraw from the partnership.’ He died about a year later. That’s one of the reasons we don’t like giving people specifics.” Weak emotional intelligence can be deadly to your investment career. If you have weak emotional intelligence, you’ll find it very difficult to buy value stocks when a good opportunity presents itself, never mind hold on to your stocks when they dip. “…you have to have a strong stomach and be willing to take an unrealized loss.” He continued in The Right Stuff , “[W]hen you buy a depressed company it’s not going to go up right after you buy it, believe me. It’ll go down.” Part of controlling your emotions means being detached to the day-to-day noise of the market. Some of the best discussion of this is found in Walter’s 1985 interview, The Right Stuff , “I try to be removed from the day to day; I don’t have a ticker-tape machine in my office………. I try to stay away from the emotions of the market. The market is a very emotional place that appeals to fear and greed… all these unpleasant characteristics that people have.” And these dangerous emotions have to be conquered if you’re going to succeed as an investor at all. To get started on your journey towards self development, I strongly recommend Daniel Goleman’s book, Emotional Intelligence . When to Sell Your Stocks A lot of investors have said that knowing when to sell is really the hardest part of investing. There are so many variables involved that knowing which stock to buy is comparatively easy. When it came to selling, Walter Schloss preferred to sell based on a sliding scale set around the firm’s intrinsic value. From Sixty-five Years on Wall Street, “…since we sell on a scale, most of the stocks we sell go up above what we sold them at. You know, you never get the high and you never get the low.” Despite that, it was important not to hold stocks that were clearly overvalued. Being a strong practitioner of Graham’s classic value strategies, Schloss was firmly committed to holding stocks that were trading well below their underlying value – even if it meant selling a start holding. From the same article, he noted, “But some times you have to take advantage of the opportunity to sell and then say OK, it’ll go higher.” Later… “We owned Southdown. It’s a cement company. We bought a lot of it at 12-1/2. Oh, this was great. And we doubled our money and we sold it at something like $28, $30 a share and that was pretty good in 2 years. When next I looked it was $70 a share. So you get humbled by some of your mistakes. But we just felt that at that level it was, you know, it was not cheap.” Selling when the time is right is a key part of classic value investing – and a lesson that I have repeatedly have had to learn. While it’s true that a depressed stock can rise in dramatic fashion, it can also dramatically disappoint investors who hold on to their stock hoping for more. Since we tend to like firms that are producing capital gains and experience pain from the stocks that drop in price, this is a critical piece of emotional temperament that investors have to get control over. From the Barron’s article, The Right Stuff , “I basically find that sometimes, if you say, “I’ll wait a while,” things don’t always work out so well. I think our biggest position is Northwest Industries. I was very pleased that they were going to distribute Lone Star Steel, and they were going to get $50 a share, and everything was great. The stock got up to over $60 a share. And suddenly the deal fell through, and now the stock’s selling at 53.” The Simple Road to Riches In February of 2012, Walter Schloss passed away at the age of 95. Despite never having a college degree, Schloss was able to forge one of the best investment records of all time. Often his home-spun wisdom seemed quaint and over simplistic. “We just buy cheap stocks,” Walter was famously quoted as saying. Yet, for a man who hung on to the investment techniques of Ben Graham for so many years, the truth of his investment principles seemed self-evident. The Walter Schloss approach to investing is indeed simple – it’s finding the stomach to implement it that’s tricky. Rather than buying cheap, ugly, hated stocks, the majority of value investors today are fumbling along in the Warren Buffett trap , trying to use a style that leverages wisdom cultivated through decades of experience. By contrast, the simple investment techniques employed by Walter Schloss proved very effective over time. They’re also much better suited for small private investors because they’re so simple to employ and are based on solid quantifiable metrics. Disclosure: I/we have no positions in any stocks mentioned, and no plans to initiate any positions within the next 72 hours. (More…) I wrote this article myself, and it expresses my own opinions. I am not receiving compensation for it. I have no business relationship with any company whose stock is mentioned in this article. Scalper1 News

Summary Walter Schloss was one of the best investors of all time. While firmly intrenched in Graham’s net-net strategy, an absence of opportunities caused him to change course. No matter whether you choose Schloss 1.0 or Schloss 2.0, his style is really easy to apply. Basically we like to buy stocks which we feel are under-valued, and then we have to have the guts to buy more when they go down. And that’s really the history of Ben Graham. That’s it.” Who do you look up to when it comes to investing? A lot of investors put their faith in Warren Buffett – and for good reason. Buffett has one of the best investment records in the industry, and has been racking up great returns for investors since the early 60s. Lesser known, but no less impressive, however, is a man that Buffett warmly refers to as “Big Walt.” When it comes to investing, Walter Schloss is a legend. Warren and Walter met at a Marshell Wells shareholder meeting, while the company traded below net current asset value, and ended up sharing an office at Benjamin Graham’s investment firm in the 1950s. Graham’s original net-net strategy has produced fantastic returns since at least the 1930s. At the time, Graham charged both with finding net-net stocks and both ended up adopting that same strategy in their own private practices years later. While Buffett eventually moved on to buying large well-protected firms in the 1970s, Walter Schloss was able to earn one of the most enviable records on Wall Street by sticking to Graham’s original framework. As Buffett put it in Superinvestors of Graham-and-Dodsville, “…He knows how to identify securities that sell at considerably less than their value to a private owner… He simply says, if a business is worth a dollar and I can buy it for 40 cents, something good may happen to me. And he does it over and over and over again. He owns many more stocks than I do – and is far less interested in the underlying nature of the business; I don’t seem to have very much influence on Walter. That’s one of his strengths; no one has much influence on him.” Schloss’ record hasn’t exactly disappointed. Over the 47 years since the closure of Graham-Newman, the high school only graduate managed to earn a solid compound annual return of 16% for his investors after management fees. While that’s an incredible 60% higher than the S&P 500, his actual portfolio returns were much better. Just how good? When Warren Buffett dubbed Schloss a super investor back in 1984, Walter had already been managing money for 28 years. According to records obtained by Buffett, Walter Schloss’ returns before management fees stood at a compound annual return of 21.3%. Not bad for a guy who never attended college! (click to enlarge) Many investors think that making money on stocks requires using advanced investment strategies, or having a 6th sense about the market, but Walter’s investment strategy was surprisingly simple. In fact, it’s so simple and so profitable that small retail investors should really pay attention. Walter Schloss on What Not to Do Many investors love to forecast the direction of the markets, but while it’s possible to guess correctly from time to time, investors have proven unable to make accurate market predictions to the extent that they just can’t be relied on to yield great returns over the long run. Walter Schloss understood this well, so stayed clear of this trap. In an article titled Setting the Right Pace , he clarified that his stance wasn’t just philosophical but stemmed from his inability to know which way the market will go, “I am not good at market timing, so when people ask me what I think the market is doing, their guess is as good as mine.” It wasn’t just market timing – Schloss also distrusted the promises of management and earnings projections. When talking about his investment in the Milwaukee Rail Road, a firm that Schloss was told would be acquired, Walter Schloss recounted, “I paid $50 a share for it because I was going to get $80. Well, that was in 1969, the market went down and the deal didn’t go through. You have to be very careful when people say they are going to do something.” On the earnings front, Discounted Cash Flow calculations applied to equities were strictly out due to the trouble estimating profits to get a solid valuation. As Walter explains, “I really have nothing against earnings, except that in the first place earnings have a way of changing. Second, your earnings projections may be right, but people’s idea of the multiple has changed. So I find it more comfortable and satisfying to look at book value.” In fact, as time passes, earnings become even more tricky to estimate. In a letter reprinted in the Harvard Business Review in 1965, Schloss wrote, “…earnings are much more likely to fluctuate than are book values, and therefore, estimating longer term earnings than, say, the next year or so can be subject to serious error.” But it wasn’t the case for Schloss that all earnings based valuations were out. In Sixty-five Years On Wall Street , he highlights which companies investors can produce plausible profit projections for and which firms they can’t, “…one of the things about these undervalued stocks… is that you really can’t project their earnings. There are stocks where there’s growth and you project what’s going to happen next year or five years. Freddie Mac or one of these big growth companies, you can project what they’re going to do. But when you get into a secondary company, they don’t seem to have that ability.” Interestingly, while most professional money managers focus on earnings, Schloss based his investment strategy on something that proved far more valuable in practice. Walter Schloss’ Ideal Investments During his early career, Walter Schloss leveraged Benjamin Graham’s famous net-net stocks strategy. From Setting the Right Pace, “I used the same investment approach I used at Graham-Newman – finding net-net stocks. It was all about capital preservation because I had to serve in the best interests of my investors.” Graham developed his net-net stock strategy after suffering devastating losses in the 1930s. His focus was on finding a strategy that would help protect an investor’s downside while providing significant upside potential. The strategy proved exceptional. While Graham found that he could produce average annual returns in excess of 20% per year by buying a hundred or so decent quality net-nets, he also found net-nets to provide good downside protection. Graham may have underestimated the strategy’s potential, however. Later studies pegged the strategy’s average annual pretax returns at between 20 and 40% . “Back in the 1930s and 1940s there were lots of stocks, like Easy Washing Machine, and Diamond T Motor, that used to sell below working capital value. You used to be able to tell when the market was too high by the fact that the working capital stocks disappeared. But for the last 15 years of so, there haven’t been any working capital companies.” While Walter Schloss and his son, Edwin, hunted for net-net stocks throughout their career, as the markets moved higher, there were far fewer net-nets on offer. To compensate for this dry spell, Schloss shifted to buying distressed firms that were trading at low prices relative to book value. From 65 Years on Wall Street, “[Our strategy has] changed because the market has changed. I can’t buy any working capital stocks anymore so instead of saying well I can’t buy ’em, I’m not going to play the game, you have to decide what you want to do.” Net-net stocks almost completely dry up during overheated markets, which can spell trouble for investors who insist on sticking to domestic securities. But, there’s always a depressed market somewhere, which gives investors willing to venture out into friendly international markets a huge advantage. Currently, Net Net Hunter members are finding the most promising opportunities in Japan . Walter Schloss Investing 2.0 Perhaps mistakenly, Schloss stubbornly stuck to North American markets, forcing him to shift his strategy. Like Buffett in the late 1960s, he just couldn’t rack up the same returns without significantly more work. But, rather than focus on growing businesses, Walter stayed true to his deep value roots with a natural extension of Graham’s net-net stock strategy. While not nearly as profitable, it still produced good returns. From a 1985 Barron’s article, The Right Stuff: Why Walter Schloss Is Such A Great Investor, “[W]e look at book value, which is a little lowering of our standards…” Schloss knew that second editions of a product were not always better. Despite the lack of net-nets, Schloss put Graham’s principles to work by buying firms for less than the value of their realizable asset values. In The Right Stuff , he explained, “You don’t have to just look at book value. You can look at what you think companies are worth, if sold. Even if it isn’t going to be sold. Are you getting a fair shake for your money?” And that’s really what Walter Schloss investing comes down to – buying a dollar for far less than it’s worth. Depending on how you employ this principle, however, understanding the business can be critical to knowing if you’re getting a good deal or not. From The Right Stuff, “I don’t understand high tech. I’m sure there are probably good buys in some of these companies that have been beaten down, but if you really don’t know, it’s better not to get involved.” By contrast, if you maintain a diversified portfolio of net-net stocks, you don’t have to have much understanding of the business at all because you’re taking advantage of the general returns offered by net-nets as a group. Key Criteria For Sleepy Value Investors Not all value investment opportunities are created equally and an investor really has to focus on the best available to yield market-beating returns. Walter Schloss focused on finding net-nets, but moved on to the next best classic value stocks available using simple criteria. In the November 1965 issue of the Harvard Business Review, Walter Schloss mentioned that, “…those companies with large book values in relation to market prices offer the stock holder the greatest rewards…” …highlighting Schloss’ preference for deeply discounted stocks. But this wasn’t the only piece of ranking criteria Schloss looked for. “[B]uy companies that don’t have very much debt, when the stock is selling at a reasonable price in relation to its assets, earnings, and dividends.” As he Highlighted in Walter Schloss: Searching For Value, low debt to equity ratios were a cornerstone of his selection process. Another key consideration were dividends. It’s common for management to think of their own bonuses before the welfare of shareholders, especially as option grants have become more widespread. As a check on mindless self-interest, Schloss also looked for dividends. “I like the idea of company-paid dividends, because I think it makes management a little more aware of stockholders…” With depressed firms, it’s particularly important that management is on the side of shareholders because these firms are often going through major business problems that management has to fix. That doesn’t mean that management has to be gifted, but they do have to have their interests aligned with shareholders. From The Right Stuff, “[T]he Cleveland Worsted fellows did own a lot of the stock, and I guess they felt the thing to do was to liquidate – which they did. Now, that’s unusual. Most companies don’t liquidate. But they were in a poor business. So they did the sensible thing. But companies don’t always do things in your interest, and you have to bear that in mind. Managements, you know, often think of themselves. It depends on the board. One of the things about business is, you try to get in with good people. You don’t have to be smart. They don’t have to be the smartest guys in the world, but you want them to be honest.” In the same article, Schloss described one firm that he thought provided an excellent example, “It’s called Potlatch and it’s a timber company out on the West Coast. It’s not spectacular, but it’s got a lot of timber, and I think the timber’s worth a lot more than the market price of the stock. Now, that’s something you have to look at the figures for see how much money they put back into these plants and so forth. One of the drawbacks to it, from some people’s point of view, is that management owns about 40% of the stock. So, a lot of people say, ‘Oh, I don’t want that; it can’t be taken over.’ But on the other hand, management has an interest in seeing that this company is a success.” He continued, “Now here’s an example of a company that’s not a book value stock, but which I think is a high-class company. It’s the old Corn Products Refining Co., CPC International. I don’t know if you know Skippy peanut butter and Mazola and Mueller’s spaghetti. ……….but those are nice consumer products. Basically, I like consumer stocks. My problem is that you pay too much for them today. They’ve been discovered, so it’s tough. CPC is not the cheapest stock in the world, but it’s got good value. It’s got book value of maybe 27, and it’s got earnings of $4 per share, I’d say. It sells at 40; the dividend is $2.20, so it’s selling at 10 times earnings. Well, you couldn’t start the business today for that. And it’s a nice steady business, not going much of anywhere, but whats the risk on the downside? ………..The stock’s never really taken off, so maybe you’d lose 10% on your money if you didn’t sell it – but that risk seems somewhat limited. Of course, they have problems. They do business in Latin America. But they have good products. So you buy it. Somewhere along the line things work out better for you.” According to Schloss, the upside was limited, but it proved to be a good parking place for his money, “I would use a price of 60 maybe, or 55 [to pegs its value at] – somewhere in that area. But the thing is, it’s a place to park money, too. ……….If this market was very low, I’d say, ‘Well, CPC probably isn’t a great stock to own. If the market is so cheap, you want to get something with a little more zip in it, or potential.’ ” Make High Probability Bets and Diversify In Sixty-Five Years On Wall Street , Schloss was lobbed the question whether he was more of a Buffett qualitative investor, or a Tweedy, Browne quant. His answer showed a lot of humility, “I’m more in the Tweedy Browne side. Warren is brilliant, there’s nobody ever been like him and there never will be anybody like him. But we cannot be like him. You’ve got to satisfy yourself on what you want to do.” He continued, “…the way that’s comfortable for us is to buy stocks where we have limited risk and we buy a lot of stocks. Well, Warren, as somebody said, owning a group of stocks is a defence against ignorance, which I actually think that’s to some extent true because we don’t go around visiting companies all over the country… ” Schloss ran a small investment shop housed in a closet in the offices of Tweedy Browne. Being a small outfit, he didn’t have the resources needed to visit companies and conduct thorough qualitative analysis. Being so small, Schloss preferred buying based on quantifiable metrics. It also never made sense to worry about what the stock would do after he bought it. In Making Money Out of Junk , he explained how deep value stocks set an investor up to capitalize on high probability, statistical, bets, “The thing about buying depressed stocks is that you really have three strings in your bow: 1) earnings will improve and the stocks will go up; 2) someone will come in and buy control of the company; or 3) the company will start buying its own stock and start asking for tenders.” Schloss continued, “The thing about my companies is that they are all depressed, they all have problems and there’s no guarantee that any one will be a winner. But if you buy 15 or 20 of them…” …they’re bound to work out well. “[I]f you buy companies that are depressed because people don’t like them, for various reasons, and things turn a little in your favor, you get a good deal of leverage.” This leverage comes partly from illiquidity and partly from shifting perceptions. Stocks are distressed because people are pessimistic about the company’s future and avoid them. Negative sentiment is often pushed to an extreme, and the stock price collapses. Since buyers avoid the stock, trading volume also dries up. This combination of low volume and a depressed stock price resembles a coiled spring held down by a finger. When something stirs in the firm’s situation which causes investors to reevaluate the company more favourably, buyers rush to purchase shares, demand outstrips supply, and the share price shoots skyward. Getting back to Walter Schloss’ three drivers of price performance, just how frequently do these events occur? In the 1960s, Warren Buffett described net-nets as working out 70-80% of the time within 2 years. Similarly, Schloss thought the odds of success for his deep value stocks were very good. In a 1985 Barron’s article titled, The Right Stuff: Why Walter Schloss Is Such A Great Investor, he explained, “About ever four years we turn over. [F]our years seems to be about the amount of time it takes. Some take longer.” But being selective about your picks is still important. As he mentioned in The Right Stuff: Why Walter Schloss Is Such A Great Investor, “The thing is, we don’t put the same amount of money in each stock. If you like something…, you put a lot of money in it.” Keep Your Head About You When All Others Lose Theirs With a little tongue and cheek, Schloss summed up in Sixty-five Years on Wall Street that the big secret of his and the rest of Buffett’s Superinvestors’ success was that none of them smoked, “I think number one none of us smoked. I think if I had to say it, I think we were all rational. I don’t think we got emotional when things went against us and of course Warren was the extreme example of that.” Psychology plays a huge role in Walter Schloss’ investment success. In fact, if Big Walt didn’t have the degree of emotional intelligence that he has, he would have never have been able to rack up the returns that he did. According to Big Walt, quoted in Walter Schloss: Searching For Value , it starts with perception, “What an investor does to some extent is based on his background. It’s very difficult to tell somebody who is fearful of stocks, ‘Yeah, you should put your money in the stock market.’ if your father lost his money in the Depression, you’ll see things differently.” Later, in the same article, he explained, “I owned some bankrupt bonds in the Pennsylvania Railroad. That would drive most people up the wall – never mind that it worked out beautifully. But people don’t want to buy bankrupt bonds.” As those who are getting free net-net stock picks already know, the same goes for Walter Schloss’ preferred deep value investments, net-net stocks. Since net-nets look scary to many investors, those with a strong emotional temperament have a powerful advantage. “One of our partners said, ‘Walter, I have a lot of money with you. I’m nervous about what you own.’ So I made an exception and said, ‘I’ll tell you a few things that we own.’ I mentioned the bankrupt rail bonds and a couple of other things that we owned. He said, ‘I can’t stand knowing you own those kinds of stocks. I have to withdraw from the partnership.’ He died about a year later. That’s one of the reasons we don’t like giving people specifics.” Weak emotional intelligence can be deadly to your investment career. If you have weak emotional intelligence, you’ll find it very difficult to buy value stocks when a good opportunity presents itself, never mind hold on to your stocks when they dip. “…you have to have a strong stomach and be willing to take an unrealized loss.” He continued in The Right Stuff , “[W]hen you buy a depressed company it’s not going to go up right after you buy it, believe me. It’ll go down.” Part of controlling your emotions means being detached to the day-to-day noise of the market. Some of the best discussion of this is found in Walter’s 1985 interview, The Right Stuff , “I try to be removed from the day to day; I don’t have a ticker-tape machine in my office………. I try to stay away from the emotions of the market. The market is a very emotional place that appeals to fear and greed… all these unpleasant characteristics that people have.” And these dangerous emotions have to be conquered if you’re going to succeed as an investor at all. To get started on your journey towards self development, I strongly recommend Daniel Goleman’s book, Emotional Intelligence . When to Sell Your Stocks A lot of investors have said that knowing when to sell is really the hardest part of investing. There are so many variables involved that knowing which stock to buy is comparatively easy. When it came to selling, Walter Schloss preferred to sell based on a sliding scale set around the firm’s intrinsic value. From Sixty-five Years on Wall Street, “…since we sell on a scale, most of the stocks we sell go up above what we sold them at. You know, you never get the high and you never get the low.” Despite that, it was important not to hold stocks that were clearly overvalued. Being a strong practitioner of Graham’s classic value strategies, Schloss was firmly committed to holding stocks that were trading well below their underlying value – even if it meant selling a start holding. From the same article, he noted, “But some times you have to take advantage of the opportunity to sell and then say OK, it’ll go higher.” Later… “We owned Southdown. It’s a cement company. We bought a lot of it at 12-1/2. Oh, this was great. And we doubled our money and we sold it at something like $28, $30 a share and that was pretty good in 2 years. When next I looked it was $70 a share. So you get humbled by some of your mistakes. But we just felt that at that level it was, you know, it was not cheap.” Selling when the time is right is a key part of classic value investing – and a lesson that I have repeatedly have had to learn. While it’s true that a depressed stock can rise in dramatic fashion, it can also dramatically disappoint investors who hold on to their stock hoping for more. Since we tend to like firms that are producing capital gains and experience pain from the stocks that drop in price, this is a critical piece of emotional temperament that investors have to get control over. From the Barron’s article, The Right Stuff , “I basically find that sometimes, if you say, “I’ll wait a while,” things don’t always work out so well. I think our biggest position is Northwest Industries. I was very pleased that they were going to distribute Lone Star Steel, and they were going to get $50 a share, and everything was great. The stock got up to over $60 a share. And suddenly the deal fell through, and now the stock’s selling at 53.” The Simple Road to Riches In February of 2012, Walter Schloss passed away at the age of 95. Despite never having a college degree, Schloss was able to forge one of the best investment records of all time. Often his home-spun wisdom seemed quaint and over simplistic. “We just buy cheap stocks,” Walter was famously quoted as saying. Yet, for a man who hung on to the investment techniques of Ben Graham for so many years, the truth of his investment principles seemed self-evident. The Walter Schloss approach to investing is indeed simple – it’s finding the stomach to implement it that’s tricky. Rather than buying cheap, ugly, hated stocks, the majority of value investors today are fumbling along in the Warren Buffett trap , trying to use a style that leverages wisdom cultivated through decades of experience. By contrast, the simple investment techniques employed by Walter Schloss proved very effective over time. They’re also much better suited for small private investors because they’re so simple to employ and are based on solid quantifiable metrics. Disclosure: I/we have no positions in any stocks mentioned, and no plans to initiate any positions within the next 72 hours. (More…) I wrote this article myself, and it expresses my own opinions. I am not receiving compensation for it. I have no business relationship with any company whose stock is mentioned in this article. Scalper1 News

Scalper1 News