Country CAPE Ratios (Part 2): Local Currency Returns

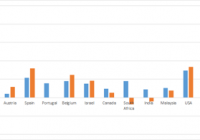

Summary In a previous article, we found that CAPE ratios did an excellent job of predicting country returns in 2013 but did a lousy job in 2014. Several commentators raised the point the analysis should have taken into account currency fluctuations. This article conducts the same analysis as before but uses local currency returns to evaluate the performance of CAPE in 2013 and 2014. Introduction The cyclically-adjusted price-to-earnings [CAPE] ratio is a commonly-used measure of valuation that has had some success in predicting long-term returns. In a chart from recent article by Hussman Funds entitled ” Does the CAPE still work? “, CAPE was found to be a reliable predictor (> 90% accuracy) of actual 10-year returns of S&P 500. The major deviations between the expected and actual 10-year returns occurred when the U.S. markets became very overvalued or very undervalued. In my previous article entitled ” Country CAPE Ratios: Wizard In 2013, Dunce In 2014? “, I mentioned the Cambria Global Value ETF (NYSEARCA: GVAL ), a fund launched in March 2014 by Mebane Faber and Cambria Investments that uses CAPE-like methodologies to invest in the cheapest markets worldwide. The timing of GVAL’s launch coincided nicely with CAPE’s fantastic performance at predicting 2013 country returns. In his “Meb Faber Research” blog , Faber presented data showing that the 5 cheapest and 10 cheapest countries posted average gains of 20.74% and 21.11%, respectively, while the 5 most-expensive and 10 most-expensive countries averaged -17.81% and -5.39%, respectively. This represents a differential of 38.59% for the 5 cheapest versus the 5 most-expensive, and 26.5% for the 10 cheapest versus the 10 most-expensive, a remarkable outperformance. Unfortunately, CAPE did a lousy job in 2014. The data showed a surprising positive correlation between CAPE and 2014 returns, meaning that the more expensive countries actually did better than the cheaper countries. I even ribbed on Faber for keeping quiet about CAPE’s performance throughout 2014, even though in 2013 Faber had enthusiastically proclaimed ” CAPE Country Returns YTD, the Ball Don’t Lie! ” a month before year-end. Perhaps Faber read my article, because he dutifully provided a CAPE update on New Year’s Day, 2015, even joking that the new edition of his book would be entitled “Global More Value.” Both Faber and my own performance data quoted USD returns. However, several astute commentators on my last article suggested that the true way to gauge CAPE should have been to use local currency returns. Therefore, this article seeks to evaluate local currency stock market performances to see if CAPE did any better in 2014 (or any worse in 2013). For the interest of consistency I will be using the same set of countries I did my previous article, even though Faber provided a more comprehensive list of country CAPE numbers in his update, which was posted after my article. 2013 Country CAPE evaluation The following table shows the 2013 return performances the various countries in both local currency [LC] and US dollar [USD] terms. Local currency returns were obtained from stock exchange performance data from the Wall Street Journal while USD returns are based on the ETFs and were obtained form Morningstar . Note that the country ETFs (often based on MSCI or FTSE indices) do not necessarily correspond to their respective stock exchanges. Country ETF CAPE at end-2012 2013LC % 2013USD % Greece GREK 2.6 28.06 24.91 Ireland EIRL 5 33.64 45.58 Argentina ARGT 5.2 88.87 15.04 Russia ERUS 7.2 -5.55 -0.88 Italy EWI 7.4 16.56 19.07 Austria EWO 8.4 4.24 11.48 Spain EWP 8.5 21.42 31.91 Portugal PGAL 9.5 15.60 – Belgium EWK 10.3 18.10 24.6 Israel EIS 11.1 15.12 18.3 Canada EWC 18.3 9.55 5.31 South Africa EZA 18.5 17.85 -7.47 India INDY 19.3 8.98 -3.99 Malaysia EWM 20.1 10.54 7.84 USA SPY 21.1 29.60 33.45 Chile ECH 21.2 -14.00 -23.9 Mexico EWW 21.2 -2.24 -1.58 Indonesia EIDO 24.7 -0.98 -23.14 Colombia GXG 33.5 -11.18 -15.01 Peru EPU 33.7 -23.63 -25.42 I compiled the total return performances into a bar chart. Countries are sorted from left to right, in order of increasing CAPE values. Local currency returns are shown as blue bars whereas USD returns are shown as orange bars. (click to enlarge) The data is also shown as a scatterplot, showing the relationship between CAPE at end-2012 and local currency returns in 2013. As with the 2013 USD returns, we see a negative relationship between CAPE at end-2012 and 2013 LC returns. The R-squared value of 0.3845 is less than the R-squared value for 2013 USD returns presented in the previous article, which was 0.5365. Nevertheless, the correlation was still significant (p-value = 0.0046). 2014 Country CAPE evaluation The following table shows CAPE values for selected countries at end-2013 and their 2014 LC and USD returns. Again, I am using the same countries as I did in my previous article. Country ETF CAPE at end-2013 2014LC % 2014USD % Greece GREK 3.8 -28.9 -38.2 Russia RSX 7.0 -12.1 -45.0 Ireland EIRL 7.3 15.1 1.9 Argentina ARGT 7.4 59.1 2.9 Jordan 8.6 Italy EWI 8.6 0.2 -9.9 Hungary 8.6 Austria EWO 9.0 -15.2 -20.1 Croatia 9.8 Lebanon 10.0 Israel ESI 10.3 10.5 0.7 Spain EWP 10.3 3.7 -4.7 Singapore EWS 11.8 6.2 2.9 Belgium EWK 12.3 12.4 1.8 Norway NORW 13.1 2.8 -22.8 Netherlands EWN 13.4 5.6 -4.7 United Kingdom EWU 13.6 -2.7 -5.9 France EWQ 14.0 -0.5 -9.9 Australia EWA 15.4 0.7 -3.8 Hong Kong EWH 16.3 1.3 4.6 Germany EWG 16.4 2.7 -10.5 Switzerland EWL 18.9 9.5 -0.8 Canada EWC 19.1 7.4 1.4 Japan EWJ 21.1 7.1 -4.4 USA SPY 25.4 11.4 11.4 And as a bar chart: (click to enlarge) We can see that for most of the countries, the 2014 local currency returns (blue bars) are higher than the 2014 USD returns (orange bar). This is likely due to the rising strength of the US dollar throughout 2014. The data are also presented as a scatterplot: As with the 2014 USD returns, we see a counter-intuitive positive relationship between CAPE values and 2014 local currency returns, but this time the correlation is much weaker (R-squared = 0.0192 compared to R-squared = 0.2664). Unlike 2014 USD returns, this correlation was not significant (p-value = 0.55). The difference between the 2014 USD and 2014 local currency results is probably due to currencies such as the Russian rouble and the Argentine peso, which fell off the cliff in 2014. Hence, local Argentine investors would have been ecstatic at their country’s 59.1% performance in 2014, whereas USD investors would be stuck with a measly 2.9% return. While this might seem like an endorsement for foreign currency hedging (particularly when it seems that every analyst and their brother is forecasting the U.S. dollar to continue to rise throughout 2015), keep in mind that predicting foreign currency movements is notoriously difficult, and that the expected value of excess returns on currencies in the long-term is basically zero. Faber himself says that it does not matter whether or not you hedge, as long as you do it fully one way or the other, as to not take a directional view on any one currency. Summary CAPE’s track record in 2014 does not look so bad once currency fluctuations are taken into account. Instead of predicting the opposite trend (more expensive countries did better on a USD basis in 2014), CAPE had no predictive power at all in 2014 for local currency returns. Nevertheless, it should be stressed that CAPE is a long-term measure of valuation, and deviations from the predicted trend should be expected as part of the natural volatility of the markets. In fact, true value investors should embrace these deviations as they might be able to buy the cheapest markets at an even cheaper price.