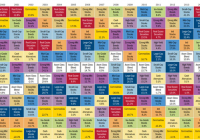

Summary We show exactly why the 60/40 allocation has provided better risk adjusted returns by evaluating 60/40 from the perspective of the enterprise. Buying stocks is buying a business, which invariably includes assumption of debt, i.e. being short bonds. Viewed in this light, actual 60/40 “net” bond exposure is significantly less than 40%. Portfolio risk is 90% from stocks and 10% from bonds, not because stocks are 9x riskier than bonds, but because your average true net dollar exposure is close to 90/10. We show historical returns for a variety of strategy combinations based on the insights of this approach, including combinations that target an “actual” net bond exposure. Targeting a true 40% bond exposure has slightly lower returns than traditional 60/40, but better risk adjusted returns with much lower drawdowns; beneficial for retirees who are making annual withdrawals. The 60/40 portfolio (60% equities, 40% bonds) has been the stalwart of the investment management industry. It has delivered better risk adjusted returns than either stocks or bonds individually since 1973. The basic idea is that some balanced combination of two non-correlated assets will provide a consistent and less volatile return stream. It has developed an aura of its own and is the go-to benchmark for other portfolio strategies to compare to. The founder of one of the large investment management firms likened it to Adam Smith’s ‘Invisible Hand,’ saying “We don’t know exactly why it works, it just always seems to work. In the end, when you look back over a 15-year period of time, it works.” Clearly, it would provide much comfort if we did understand why it worked, and this article will shed some light on how 60/40 works in a way you have probably not seen before. Going back to Basics First To understand the concept in its simplest sense, we need to cover some basics of investing across the capital structure. The graphic below shows the enterprise triangle, with the various levels of participation that an investor can choose from. Bonds are the least risky form of investment in the enterprise because they have the highest priority claim against the assets of the business. Equity carries the highest risk because it is the last to get paid after all other stakeholders have been paid. By definition, you should expect a higher return from equity than debt because it carries more risk. Except for government debt, all other debt and equity are dependent on the performance of the enterprise. (click to enlarge) Key concept When investing in stocks, you are buying an ownership interest in the whole enterprise. This means that you also assume (not personally) the debts of the enterprise. Assuming debt or borrowing is the opposite of lending, investing or being long. Borrowing is therefore the same as being short debt. Investing in equities of companies that have debt therefore creates two risk exposures, 1) long equities and 2) short debt. The following box shows an example of creating a 60/40 portfolio at the simplest level. Assume company SPX, representing the entire investment universe, has a market cap of $600,000 and has debt outstanding of $400,000. Assume further that your portfolio of $1,000,000 is currently in cash and ready to be invested in a 60/40 portfolio. (click to enlarge) There are two transactions necessary, 1) allocating 60% of your capital to stock, and 2) 40% to bonds. In Transaction #1, when you buy the equity in a company you automatically assume (not personally) the debt of that company. The debt as a percent of the market cap is 66.7% ($400,000/$600,000). Assuming the debt, as explained above is the same as being short the debt, so your exposure from Transaction #1 is to be long $600,000 in equities and short $400,000 in debt. In Transaction #2, you allocate 40% of your $1,000,000 to bonds. By investing $400,000 in the bonds of the company, you have effectively neutralized your bond exposure. Your net bond exposure is now zero . Obviously, the investment universe is a lot more diverse than just our company SPX, including government debt, but hopefully you get the concept of your “net debt” exposure. We will use the terms net debt, net bond and net leverage exposure interchangeably. Extrapolating the concept to the real world Most 60/40 portfolios will invest the equity portion into a diversified fund or ETF that tracks the entire market such as the SPDR S&P 500 Trust ETF (NYSEARCA: SPY ) or the Vanguard S&P 500 ETF (NYSEARCA: VOO ). When you purchase the SPY, you are by definition assuming the total debt of all those companies in the same proportion to your equity ownership. How do you know how much debt you are assuming? The Federal Reserve Z1 makes this data available on a quarterly basis. It shows the total credit market liabilities as a percentage of the market value of equities outstanding (debt/market cap ratio). Here is the chart since 1953. (click to enlarge) You will notice that the amount of debt that companies hold relative to the market value of their equity is not constant. For every dollar you have invested in equities, you are effectively short bonds in the amount of $1 x debt/market cap ratio percentage, shown on the vertical axis of the graph. This would be offset by your 40% long investment in bonds. Based on this, we can show the net debt exposure for a 60/40 portfolio, rebalanced annually, going back 40 years to 1973. Key Takeaways Net debt exposure is not constant with 40% in bonds. Net exposure will differ depending on the debt/market cap ratio, and it changes continuously. Over 40 years, the 60/40 portfolio, rebalanced annually, had only 3.01% net exposure to bonds . From 1974-1993, net exposure averaged -7.73% and from 1994-2014 was a positive 13.25%. This exposure worked out well for 60/40 investors because it was generally short debt in the rising interest rate environment and long debt in the declining interest rate environment. The often cited fact that stocks in a 60/40 represent 90% of the risk is true, but not because stocks are 8-9 times riskier than bonds, but because the true net dollar exposure of bonds has been less than 10%. Dollar allocation does approximate risk allocation when you think about it in this framework. 60/40 has worked by essentially maintaining a relatively unlevered exposure to the enterprise. Note that while we have assumed all debt is corporate debt, in reality a large portion of the 40% gets allocated to government debt. While the risk profiles are somewhat different, the net bond exposure is the same, and the performance over 40 years is very similar. The Mechanics of Rebalancing The mechanics of rebalancing, which we show below, are a bit complicated, but in a nutshell, when equities go down relative to bonds you increase your risk profile at rebalance time, and when equities go up relative to bonds you reduce your risk profile at rebalance time. The transactions that occur at rebalance time are shown below for two scenarios, 1) equities go down relative to bonds, and 2) equities go up relative to bonds. The dynamics change slightly depending on how you treat the book value of debt. Does it go to market or stay at book? We show it both ways. In Scenario #1, when equity values decline, the debt/market cap ratio increases, increasing your short debt exposure at the enterprise level, making your portfolio more volatile; rebalancing increases your equity exposure, and your implied short debt exposure (both of which contribute to increasing your risk profile), which is then offset by the increased allocation to your long debt exposure. Like I said, it’s a bit complicated. The bottom line of each table shows the new net debt exposure. If you are interested in the workings, then review the tables below else skip ahead to the next section. Questions and Possibilities There are literally dozens of possibilities that arise in thinking around this idea, but I want to give you some actionable insights, so I will highlight a few possibilities and show a range of performance comparisons to finish. Can we replicate the 60/40 risk profile by just investing 100% of the portfolio in equities of a basket of unlevered, or low levered companies? There is no index that we know of that tracks exclusively low leverage; some include leverage as a factor in their quality index. Berkshire Hathaway (NYSE: BRK.A ) (NYSE: BRK.B ) almost fits the bill, and we show the performance, but Buffett is an anomaly, so we cannot assume similar performance. Risk is not only a function of leverage, but also industry and size, so expecting low leverage alone to match the risk profile of 60/40 is not realistic. The S&P Low Volatility Index (implement with SPLV) does have about 25% less leverage than the S&P 500, so we show those returns both individually and in combination with 20% government bonds. As an investor, you have the choice of deciding how much net leverage you are comfortable with. You can adjust your bond exposure to achieve this. We show the performance of a portfolio that targets 0% net bond exposure, and one that targets 40% net bond exposure. It turns out that 60/40 outperforms any positive target debt level we could find, but on a risk adjusted basis, the true 40% bond target does much better. While there is some benefit to government bonds, over 40 years the difference between using corporate and government is very small – corporate has a slightly higher return, but government has slightly better risk adjusted returns. Corporate bonds are exposed to the enterprise risk, so for diversification you may prefer more exposure to government bonds. Government bonds provide that flight to safety when the future of the economic enterprise looks risky, even though corporate bonds seem to have performed better individually. We show the traditional 60/40 with both government and corporate bonds. Performance Comparisons The following table shows returns for stocks, government bonds, corporate bonds, low volatility, and Berkshire, individually, and then in a series of different combinations, including 60/40 conventional with T-bonds, 60/40 with corporate bonds, 0% net bond target, 40% net bond target, and 80% low vol/20% government bonds. Years in which stocks had negative returns are highlighted in red to easily see how each strategy performs under those conditions. While I will leave you to peruse these without comment, I just want to highlight the performance of the “true” 40% net bond exposure versus the traditional 60/40 (both circled); it has slightly lower returns but much better risk adjusted returns and the drawdowns are much smaller. This can be especially beneficial for retirees who are withdrawing assets from their portfolio every year to live on. Conclusion This article just scratches the surface, and there are many portfolio construction possibilities to explore around this idea. Viewing 60/40 from an enterprise value perspective offers a better insight into your risk profile characteristics. Targeting a true 40% long bond exposure gives a lower absolute return than traditional 60/40, but much better risk adjusted returns, with much lower drawdowns. Disclosure: The author has no positions in any stocks mentioned, but may initiate a long position in SPY, VOO, TLT, AGG, LQD, SPLV over the next 72 hours. (More…) The author wrote this article themselves, and it expresses their own opinions. The author is not receiving compensation for it (other than from Seeking Alpha). The author has no business relationship with any company whose stock is mentioned in this article.