How To Build A ‘Lifetime’ Portfolio (Step 1)

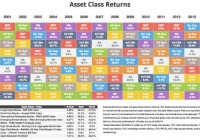

Why obsess about what will happen this coming week? That’s the job of people who get paid by the word. Why not take the road less traveled and ignore 90% of the hullabaloo?!! This is the time of year when most investment writers predict what will happen in 2015. What I’d rather offer, however, is what is “most” likely to happen this year, next year, or the next 10, 20 or 50 years. The short and glib answer is the one proffered by J.P. Morgan when asked what the market would do next. “It will fluctuate,” he replied. That may sound offhandedly dismissive of the question, but in fact there is much truth, and the beginnings of what we now call Modern Portfolio Theory (MPT) in his pithy response! Modern Portfolio has much to recommend it and much to eschew. The basic idea is solid: MPT is a way to optimize your returns based on your acceptable level of market risk. You accomplish this by diversification among various asset classes. If you can remember as far back as January 2014, almost every pundit was predicting a disastrous year for bonds, a so-so year for US stocks to digest the gains of 2013, and sector bets all over the place. I don’t know of a single analyst who predicted that the best-performing sector in the USA would be utilities, yet there they are, proudly atop all markets. The matrix below shows what asset class performed best over the past few years. (These are asset classes, not business sectors, so you won’t see utilities there, but you will see “REITs” and both “High Grade” and “High Yield” bonds, both of which are equally-interest-rate-sensitive.) If you look carefully at every year, you will note the results vary considerably. The same holds true over all other, even more extended, periods. Diversification works! Yes, you will sometimes fail to beat the market, “market” being shorthand to most investors for the “Large Caps” represented by the S&P 500, but over most periods other than an out-and-out bull romp in US stocks that means you are likely to do much better. (click to enlarge) You’ll note, for instance, that in 2000, the large caps, as measured by the S&P 500, were the 3rd- worst performing asset class. In 2002, they were “dead last.” In fact, if you look closely, you’ll note that not once was the S&P 500 the top-performing asset class – including the past 6 remarkable years! Being open to other asset classes is the heart of Modern portfolio Theory, but also the heart of Asset Allocation theory, and the heart and soul of our approach to building a Lifetime Portfolio. In a period of low and declining or stable interest rates, the aforementioned utilities, bonds and REITs often outperform stocks, and with considerably less volatility and heartburn. MPT has also become associated with the notion that, since no one can predict what will happen on any given market day (or week, month, year, etc.) why bother? Why not instead select the asset classes that give you a level of risk you are comfortable with and then get reasonable returns year in and year out? Rigorous academic research shows that you will typically come out ahead after even a few years of doing this than you will if you try to “beat the market.” To oversimplify: if your risk tolerance is low, you might create a portfolio of 40% high grade bonds, 20% REITs, 20% high yield bonds and 20% large cap stocks. If you are comfortable seeking greater returns with greater risk, you might select 10% each of high grade and high yield bonds and REITs, with the other 70% of your portfolio split among US Large and Small Caps, International Large and Small Caps, and Emerging Markets. In any scenario you construct, you want to let your profits grow while feeding the areas you have selected that aren’t doing as well. The usual way this is done is to rebalance at some defined period every year (or less). A variation of this is to pick a certain percentage, say 20%, and if one asset class gets “out of whack” by that amount you add to it if it is down, or sell off some of it if it exceeds the 20% higher than your chosen percentage allocation. If you wanted to hold 20% of your portfolio in large caps, for instance, if that asset class appreciates 20% and is now therefore 24% of your total portfolio (20% of 20 is 4), you would “re-balance” to bring that part of the portfolio back to your risk comfort level, using the proceeds to buy, at lower cost, some of the other asset classes that are “currently” lagging. Does this sound boring? It may be, but which sounds better: a 7.4% annual return over 14 years or a 4.3% return? The bottom line on the above chart is that the simplest asset allocation plan imaginable, 40% high grade bonds, 15% each U.S. large caps and international stocks, and 10% each of small caps, emerging markets and REITs, rebalanced annually, still beat the currently-in-vogue “just buy an S&P 500 index fund; active management doesn’t work” mantra. This “just buy an S&P 500 index fund; active management doesn’t work” fable becomes popular once we are well ensconced in a bull market – and dies just as quickly when the market plummets. As the data above shows, the drawdown for the S&P 500 was -37% in 2008. The biggest drawdown for the asset allocation model (AA) was -22.4%. For comparison, our Growth and Value portfolio, in which we used our own variations on asset allocation described below, was down 18.7% that year. On a million dollar portfolio, the S&P would have declined in value to $670,000; our G&V to $813,000, with less position risk and less volatility. How We Diverge From the Standard Model There are scores of ways you might select an asset allocation model that works for you, from changing the percentage allocations to increasing the asset classes to adding a little sentiment, fundamental, historic or technical analysis. We try not to sway too far from the basic principles of asset allocation. We like to think we are merely adding a dollop of common sense and placing history on our side. We believe: Rebalancing based on the calendar is folly. In the chart above, the results tabulated are for a rebalance once a year at the beginning of each year. Macro-trends evidence themselves any time of the year; both black and white swans swoop and dive based upon events, not calendars. We take action when our asset allocation percentages diverge from our intended allocation. Underlying the concept of asset class investing is the assumption that markets are efficient and that investors act rationally. We might give some credence to the first assumption, but the second is patently false! We believe we can benefit from investor emotions. An example today might be early nibbling at the huge integrated oil companies that can slash CapEx and make a profit on their current properties if the price of oil falls even another 50%. Buy them when they’re cheap; don’t obsess if something you buy for 10 times forward earnings and a 5.9% yield falls so that you “might have” bought it at 8 times forward earnings and a 6.4% yield. At times when interest rates are rising, we might be as little as 0-20% in bonds and REITs combined. When falling, we might be at 60-70%. We are dynamic, not static. [This is a very big divergence from the academics’ idea of asset allocation. That’s their way; this is our way.] “To every thing there is a season.” We augment our asset class investing to take advantage of the fact that small caps tend to enjoy the bulk of their outperformance in the first two quarters of the year, that pre-presidential election years are often excellent market years as both parties crank up the PR machines, etc. We don’t chase any single asset class like S&P 500 large caps, REITs, small caps or any other. Nor do we obsess if we fall behind in comparison to any one asset class for an extended period. We maintain our discipline and do our best to grow our portfolios steadily. Sometimes we have setbacks, sometimes we are out of sync, but we’ve always bounced back. In Part II, I will discuss the asset classes that are historically most and least correlated with the S&P 500 (U.S. large caps) and with each other, so you can begin to consider how you might construct a Lifetime Portfolio that works for you. I’ll also discuss the types of mutual funds and ETFs our research and analysis leads us to, including examples and some of our specific current holdings. As Registered Investment Advisors, we believe it is our responsibility to advise that we do not know your personal financial situation, so the information contained in this communiqué represents the opinions of the staff of Stanford Wealth Management, and should not be construed as personalized investment advice. Past performance is no guarantee of future results, rather an obvious statement but clearly too often unheeded judging by the number of investors who buy the current #1 mutual fund one year only to watch it plummet the following year. We encourage you to do your own due diligence on issues we discuss to see if they might be of value in your own investing. We take our responsibility to offer intelligent commentary seriously, but it should not be assumed that investing in any securities we are investing in will always be profitable. We do our best to get it right, and we “eat our own cooking,” but we could be wrong, hence our full disclosure as to whether we own or are buying the investments we write about.