Frustrated Yet?

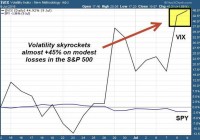

The last year has been a tough one for investors. There are a few places one could have booked a double-digit gain in the last 12 months but not many and certainly not in assets that are in the standard portfolio. Currency hedged ETFs for European and Japanese stocks produced big gains, but a lot of the gain was from nothing but currency movements. And most investors shouldn’t be trying to make their yearly return punting on currencies. Stocks for the most part have been disappointing with Nasdaq as a notable exception. Notable because a lot of the action there is reminiscent of the last time that index was leading the market back in 1999/2000. The recent big moves in Google (NASDAQ: GOOG ) (NASDAQ: GOOGL ), Netflix (NASDAQ: NFLX ) and Amazon (NASDAQ: AMZN ) – based on not much – provided a eerie sense of deja vu for anyone who lived through that giddy time. The S&P 500 over the last six months is barely positive, up about 2% (or it is as I write this Friday afternoon; but if things keep going in the current direction, that could be a lot closer to 0 by the close). The average doesn’t do justice to what is really going on though. Only about half the stocks in the S&P 500 are trading above their 200-day moving average right now. Even for an index like the Nasdaq that has performed pretty well this year, less than half the stocks in the index are still in uptrends, trading above their 200-day MA. These are capitalization weighted indexes and at least right now, size does seem to matter. A similar message is sent by the advance/decline stats which show the decliners winning by a pretty wide margin. New highs/new lows also looks less than healthy with new highs increasingly scarce. So the internals of the stock market are deteriorating notably, something that doesn’t generally bode well for the immediate future for stock prices. There are other signs of stress as well. Junk bonds essentially peaked almost a year ago in price and have been trading sideways with a downward bias which has recently accelerated. With Treasuries generally well bid all week, the spread between junk and Treasury yields widened on the week, continuing the longer-term trend that started last summer and reversing the shorter-term narrowing trend that started at the beginning of this year. Credit spreads are highly correlated with the stock market, so ignore the junk market at your portfolio’s peril. Other signs of stress have emerged over the last couple of weeks. Commodities have resumed their downtrend and unlike some other recent periods, it isn’t just a function of a rising dollar. The dollar has been fairly steady but was down last week even as gold and other commodities plumbed new lows for the move. Oil is breaking toward its lows and that is undoubtedly the source of at least some of the selling in the junk bond market. The fracking companies are still struggling and lower prices aren’t going to help them make their interest payments now that their hedges are expiring. The Treasury market also is pointing to some stress with inflation and growth expectations both falling a bit recently. The frustration of the diversified investor actually goes back quite a bit further than the last 6 months or last year. If you have been following an investment plan that includes international stocks and bonds, a smattering of commodities and/or anything else that isn’t US stocks, your personal pain is now running into more like two years and maybe a bit more. I track a long list of passive portfolios and many of the globally diversified ones are working on their third consecutive year of low-to-mid single-digit returns – assuming this year turns out to have a positive number. It isn’t just the US stock indexes that have been narrowing; it is the entire investment universe. This winnowing of the investment universe to a few winners, turning diversification into a risk factor, is just one more example of the negative consequences of the modern form of economics in which common sense has been relegated to quaint notion and nonsense elevated to learned discourse. It is an Orwellian discipline where borrowing and spending have replaced thrift and investment as the drivers of economic growth, prudence is punished, speculation celebrated and rewarded. Is it any wonder that our economy continues to struggle when we’ve spent decades urging the population to be irresponsible, to ignore the future so that our present can be more comfortable? Monetary policy is a cudgel, a blunt tool used for more than a mere nudge, to make investors feel obliged to chase returns, to take excessive risks to achieve even their mundane goals. If you can’t achieve those goals with safe investments – and economic policy has made that nigh on impossible – you move out on the risk scale until you can because the alternative – spending less, saving more – has been deemed un-American, economically unpatriotic. The unspoken agreement – unspoken by the Fed certainly but widely accepted and believed – is that the monetary powers that be will maintain risky assets at the high prices that have, according to the Fed, produced or at least enhanced whatever meager recovery we’ve had since 2009. A permanently high plateau , if you will. The problem is that this unspoken agreement, this economic wink and a nod, has produced moral hazard on an epic scale. People do stupid things when they think their rewards are deserved and any losses will be absorbed or prevented by others. If you doubt that, just take a few moments to remember the structure of the mortgage system that produced the last crisis. It was a system where government policy didn’t just implicitly relieve lenders of the risks of their loans, they did it explicitly by either guaranteeing the loans or buying them outright. Now we apply that lesson to all investors, the Fed equally concerned about the stock index and the price index. It has “worked” so far in that risky asset prices are high but the economic payoff is less clear. It may be that the US and global economy is better off today than it would have been without the exertions of the world’s central bankers, but you’d be hard pressed to prove it. Considering the moral lessons being taught by these policies one can’t help but wonder if the gains are worth the potential losses. Markets, individuals, will eventually see through the Fed’s illusion of control and mark assets to a real market. The list of winning investments – risky investments – has been pared down to just a few over the last two years and the list gets shorter every day. Most recently the junk bond market has been quietly deleted or at least partially erased from the winners list. With oil prices falling again, the fracking companies bankers are balking of course, but it isn’t just energy companies that are being denied financing. Several deals have been canceled recently that had nothing to do with fracking. And it isn’t just junk bonds that are getting marked down; the high grade corporate bond ETF (NYSEARCA: LQD ) has actually performed worse than its junk bond cousin over the last six months. You certainly can’t call it a credit crunch yet but the new normal economy may not need a full blown crunch to fall into recession. It is a frustrating time for investors and one that is fraught with danger. The risk isn’t from without, from some unknown black swan, but rather from within, from ourselves, the self-inflicted financial wound caused by greed and the very American desire to win, to do better than the next guy. It is tempting to discard the investment methods that have withstood the test of time in favor of the fad of the moment, the church of what’s working now. But in every investment cycle there comes a time when winning is accomplished by not losing, by ignoring the sirens of risk and lashing oneself to the mast of safety. Now would seem a good time to at least find the rope.