Why EPS And Share Price Don’t Predict Future Performance

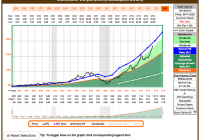

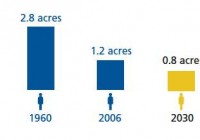

Most analysts, and especially “chartists,” put a lot of emphasis on earnings per share (EPS) and stock price movements when determining whether to buy a stock. Unfortunately, these are not good predictors of company performance, and investors should beware. Most analysts are focused on short-term – meaning quarter-to-quarter – performance. Their idea of long term is looking back 1 year, comparing this quarter to the same quarter last year. As a result, they fixate on how EPS has done and will talk about whether improvements in EPS will cause the “multiple” (meaning stock price divided by EPS) to “expand.” They forecast stock price based upon future EPS times the industry multiple. If EPS is growing, they expect the stock to trade at the industry multiple, or possibly somewhat better. Grow EPS, hope to grow the multiple, and project a higher valuation. Analysts will also discuss the “momentum” (meaning direction and volume) of a stock. They look at charts, usually less than one year, and if price is going up, they will say the momentum is good for a higher price. They determine the “strength of momentum” by looking at trading volume. Movements up or down on high volume are considered more meaningful than those on low volume. But unfortunately, these indicators are purely short-term, and are easily manipulated so that they do not reflect the actual performance of the company. At any given time, a CEO can decide to sell assets and use that cash to buy shares. For example, McDonald’s (NYSE: MCD ) sold Chipotle and Boston Market. Then, the leadership took a big chunk of that money and repurchased company shares. That meant McDonald’s took its two fastest-growing and highest-value assets and sold them for short-term cash. They traded growth for cash. Then leadership spent that cash to buy shares, rather than invest in another growth vehicle. This is where short-term manipulation happens. Say a company is earning $1,000 and has 1,000 shares outstanding – so its EPS is $1. The industry multiple is 10, so the share price is $10. The company sells assets for $1,000 (for the purpose of this exercise, let’s assume the book value on those assets is $1,000 – so there is no gain, no earnings impact and no tax impact.) Company leadership says its shares are undervalued, so to help out shareholders it will “return the money to shareholders via a share repurchase” (Note, it is not giving money to shareholders, just buying shares.) $1,000 buys 100 shares. The number of shares outstanding now falls to 900. Earnings are still $1,000 (flat, no gain), but dividing $1,000 by 900 now creates an EPS of $1.11 – a greater than 10% gain! Using the same industry multiple, analysts now say the stock is worth $1.11 x 10 = $11.10! Even though the company is smaller has weaker growth prospects, somehow this “refocusing” of the company on its “core” business and cutting extraneous noise (and growth opportunities) has led to a price increase. Worse, the company hires a very good investment banker to manage this share repurchase. The investment banker watches stock buys and sells, and any time he sees the stock starting to soften, he jumps in and buys some shares so that momentum remains strong. As time goes by and the repurchase program is not completed, he will selectively make large purchases on light trading days, thus adding to the stock’s price momentum. The analysts look at these momentum indicators, now driven by the share repurchase program, and deem the momentum to be strong. “Investors love the stock”, the analysts say (even though the marginal investors making the momentum strong are really company management), and start recommending to investors that they should anticipate this company achieving a multiple of 11 based on earnings and stock momentum. The price now goes to $1.11 x 11 = $12.21. Yet, the underlying company is no stronger. In fact, one could make the case it is weaker. But due to the higher EPS, better multiples and higher share price, the CEO and her team are rewarded with outsized multi-million dollar bonuses. But over the last several years companies did not even have to sell assets to undertake this kind of manipulation. They could just spend cash from earnings. Earnings have been at record highs – and growing – for several years. Yet, most company leaders have not reinvested those earnings in plant, equipment or even people to drive further growth. Instead, they have built huge cash hoards , and then spent that cash on share buybacks, creating the EPS/multiple expansion – and higher valuations – described above. This has been so successful that in the last quarter, untethered corporations have spent $238B on buybacks, while earning only $228B . The short-term benefits are like corporate crack, and companies are spending all the money they have on buybacks rather than reinvesting in growth. Where does the extra money originate? Many companies have borrowed money to undertake buybacks. Corporate interest rates have been at generational (if not multi-generational) lows for several years. Interest rates were kept low by the Federal Reserve hoping to spur borrowing and reinvestment in new products, plant, etc. to drive economic growth, more jobs and higher wages. The goal was to encourage companies to take on more debt, and its associated risk, in order to generate higher future revenues. Many companies have chosen to borrow money, but rather than investing in growth projects, they have bought shares. They borrow money at 2-3%, then buy shares – which can have a much higher immediate impact on valuation – and drive up executive compensation. This has been wildly prevalent. Since the Fed started its low-interest policy, it has added $2.37 trillion in cash to the economy. Corporate buybacks have totaled $2.41 trillion. This is why a company can actually have a crummy business and look ill-positioned for the future, yet have growing EPS and stock price. For example, McDonald’s has gone through rounds of store closures since 2005, sold major assets, now has more stores closing than opening and has its largest franchisees despondent over future prospects . Yet, the stock has tripled since 2005! Leadership has greatly weakened the company and put it into a growth stall (since 2012), and yet, its value has gone up! Microsoft (NASDAQ: MSFT ) has seen its “core” PC market shrink, had terrible new product launches of Vista and Windows 8, wholly failed to succeed with a successful mobile device, has written off billions in failed acquisitions, and consistently lost money in its gaming division. Yet, in the last 10 years, it has seen EPS grow and its share price double through the power of share buybacks from its enormous cash hoard and ability to grow debt. While it is undoubtedly true that 10 years ago Microsoft was far stronger as a PC monopolist than it is today, its value today is now higher. Share buybacks can go on for several years. Especially in big companies. But they add no value to a company, and if not exceeded by re-investments in growth markets, they weaken the company. Long term, a company’s value will relate to its ability to grow revenues and real profits. If a company does not have a viable, competitive business model with real revenue growth prospects, it cannot survive. Look no further than HP (NYSE: HPQ ), which has had massive buybacks, but is today worth only what it was worth 10 years ago as it prepares to split. Or Sears Holdings (NASDAQ: SHLD ), which is now worth 15% of its value a decade ago. Short-term manipulative actions can fool any investor and keep stock prices artificially high, so make sure you understand the long-term revenue trends and prospects of any investment, regardless of analyst recommendations.