Sell The State, Buy The People

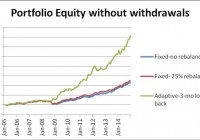

Summary State-owned companies dominate many emerging-market ETFs. State-owned companies generate lower return on assets than privately-managed firms. Avoiding the slower-growing state firms by going with small caps, or a fund such as XSOE. Investors can slice and dice the investment world into all manner of categories. One of the most common is to separate its investments into domestic and international, developed and emerging markets, then into regions or individual countries. A different way to slice the market is to break it down into state-owned and private companies. This is not a critical distinction for investors in the developed world, where deep capital markets offer exposure to many private firms, but many emerging markets are still developing their capital markets. A passive investment approach in emerging markets results in a state-owned heavy portfolio, but there are ways to avoid this exposure. State Interference Doesn’t Pay At least since Ludwig Von Mises published Economic Calculation in the Socialist Commonwealth , the case against socialist economic planning has been there for those who choose to look. Without information, an enterprise cannot make good decisions, and one of the first casualties of central planning is the informational content in prices. Prices exist in centrally-planned economies, but they do not reflect the supply and demand in the economy. The unfolding disaster in Venezuela, a country that suffered toilet paper shortages and is now occupying supermarkets with the army in its never-ending war against the laws of economics, is only the latest example of this basic truth. Clearly, one does not want to invest in a basket case such as Venezuela. At the other end, one cannot avoid some intervention in the economy, as nearly every nation on Earth has a central bank working to manipulate interest rates. In between are the mixed economies such as in China, where the transition to market capitalism is still incomplete. These countries have varying degrees of market forces, but one common trait in many is that state-owned enterprises (SOEs) compete alongside private firms. In many of those countries, the state-owned giants dominate the stock market and make up the bulk of market capitalization. The extreme case is China, where most of the listed companies on the mainland stock exchange are SOEs. In Brazil, semi-private Petrobras (NYSE: PBR ) has accounted for 20 percent of stock market capitalization alone. As oil prices have tumbled and PBR sees corruption charges swirl around the firm , investors in funds such as iShares MSCI Brazil (NYSEARCA: EWZ ) have paid the price. Investors who passively plunk money into market capitalization index funds are often unknowingly choosing to invest with the state and even where the firms are increasingly competitive, they still often lag behind fully-privatized competitors. Recent figures show that Chinese SOEs earn about 5 percent on assets , versus roughly 9 percent for private firms. SOEs in China achieve this low return despite access to cheap credit and regulatory favoritism, in part because the largest shareowner, the state, cares about many things besides profit. Additionally, the government officials in charge of these firms have their own private agendas, and those often stray into the realm of corruption. Some recent examples are the lackluster performance of Russian energy firms even when oil prices were high, Chinese banks that have run up a mountain of bad debt due to politically-motivated lending, and as mentioned above, Brazil’s largest company is racked with scandal. Aside from the aforementioned issues, there’s the issue of sector exposure. Many state-owned companies are banks, energy producers, utilities and telecom firms. While these companies can experience rapid growth in a rapidly-growing economy, they aren’t growing as fast as technology start-ups and new consumer companies catering to an emerging and increasingly wealthy middle class. Investment Options There are some ways around this, the easiest of which is to go with small caps, though that involves taking on more volatility. Broad small-cap ETFs, such as WisdomTree Emerging Markets SmallCap Dividend (NYSEARCA: DGS ), reduce exposure to SOEs. Guggenheim China Small Cap (NYSEARCA: HAO ) and Market Vectors Brazil Small Cap (NYSEARCA: BRF ) both offer a different mix of sector exposure along with avoiding the giant SOEs that populate many emerging-market ETFs. Some sector ETFs, such as KraneShares CSI China Internet (NASDAQ: KWEB ) achieve the same result. WisdomTree Emerging Markets ex-State-Owned Enterprises (NYSEARCA: XSOE ) WisdomTree launched XOSE in December to help investors maintain emerging market exposure while avoiding state-owned companies. The case for the fund is straightforward: the growth of emerging markets is the story of a rising middle class. The sectors most poised to benefit are those that serve these customers: consumer staples, consumer discretionary and healthcare firms. Technology is also an emerging sector in many of these countries that is growing far faster than the overall economy. To really profit from the growth of emerging markets, investors want to be positioned in the sectors pulling GDP forward, not the moribund state-owned enterprises that lag behind or at best, are indirect plays on the commodity cycle. From WisdomTree’s website : (click to enlarge) Technology is the largest sector exposure at nearly 23 percent of assets. Healthcare is underweight, consumer discretionary and consumer staples are the third and fourth largest sectors. Financials are a large portion of assets at about 20 percent, but that is less than many emerging market funds. One reason why the fund isn’t better positioned with respect to sectors is because the fund’s main goal is the removal of SOEs, not a shift in sector exposure. From WisdomTree, the index criteria (emphasis mine): ” State owned enterprises are defined as government ownership of more than 20% of outstanding shares of companies. The index employs a modified float-adjusted market capitalization weighting process to target the weights of countries in the universe prior to the removal of state owned enterprises while also limiting sector deviations to 3% of the starting universe. ” For investors who want to remove SOE exposure while still getting similar sector and country exposure as the run-of-the-mill emerging-market fund, XSOE is a great choice. Assuming the state-owned companies aren’t reformed and unlock hidden value from their assets, over time XSOE should beat the market capitalization weighted competition such as iShares MSCI Emerging Markets (NYSEARCA: EEM ). The case for owning XSOE over other funds is stronger today because the sectors dominated by SOEs are at the center of the slowdown in emerging markets, from China’s debt-laded banks to Brazil and Russia’s energy-heavy stock markets. The fund might lag for long periods when plain vanilla emerging market funds benefit from the sector exposure that SOEs bring, but over the long run, XSOE is likely to come out ahead thanks to holding shares in more efficient firms. Disclosure: The author has no positions in any stocks mentioned, and no plans to initiate any positions within the next 72 hours. (More…) The author wrote this article themselves, and it expresses their own opinions. The author is not receiving compensation for it (other than from Seeking Alpha). The author has no business relationship with any company whose stock is mentioned in this article.