5 Questions On Risk In Concentrated Equities Today

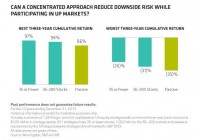

By Mark Phelps & Dev Chakrabarti As equity markets cope with fresh volatility from China to Europe, managing risk is a top priority. In our view, concentrated portfolios stand up to scrutiny on risk – even in today’s complex market conditions. Concentrated portfolios are a popular way to capture high conviction in equities. But many investors worry that by focusing on a small number of stocks, they may be more vulnerable when volatility strikes. These five questions can help gauge whether that’s really true. 1. Is a concentrated equity portfolio more vulnerable to a market correction than a diversified portfolio? Not necessarily. Based on our experience – and academic studies – we believe that concentrated portfolios can actually cushion the damage in a market correction. Since concentrated managers have much more to lose than managers of diversified portfolios if a single stock underperforms, they tend to be much more focused on the earnings risk of individual holdings and of the portfolio. Our research on US equity strategies supports this notion. We followed up on the famous study by Cremers and Petajisto* and found that the median concentrated US equity manager, with 35 or fewer stocks in a portfolio, incurred less severe losses than diversified portfolios in down markets. This made it easier to recoup losses on the way back up. As a result, concentrated strategies posted stronger three-year returns than traditional active and passive strategies over the 10-year period studied (Display). And during the worst three-year period, the portfolios of concentrated managers declined less than other active and passive portfolios. 2. Why isn’t a concentrated portfolio more vulnerable to market surprises? Portfolios with small numbers of stocks by definition have a high active share and diverge from the benchmark substantially. This can be a good thing when surprises rattle the market. Benchmarks give investors exposure to volatile sectors, especially in down markets. For example, both energy and financials are sectors that are notoriously unstable. So constructing a portfolio that is less exposed to those sectors would tend to protect against vulnerability in those markets. In the oil-price shock of the last year, a diversified portfolio with weights that are closer to the benchmark is more likely to have greater exposure to the energy sector than a concentrated portfolio. And in financials, many pure banks are too risky for a concentrated portfolio, in our view, because it’s simply too difficult to forecast earnings that are tied to the uncertainties of the future rate environment. 3. Does that mean a concentrated portfolio will miss out on a big sector recovery? It’s true that volatile sectors do lead the market at times. But over the long term, we believe it’s better to focus on a few select holdings that provide alternative ways to gain selective exposure to a sector recovery. For example, some financial exchanges or asset management firms have much lower capital intensity than pure banks – and offer better return potential driven by secular trends in their industries, in our view. Focusing on stocks that have shown consistency of earnings through good and bad periods is a more prudent path to generating long-term returns than taking big sector overweights, which may be prone to instability. 4. How can regional risk be managed in a global portfolio with so few stocks? While concentrated managers always focus primarily on stock-specific issues, monitoring regional exposure is important. Stock-picking decisions must also ensure that the sum of a global portfolio’s parts is balanced and appropriately positioned for macroeconomic conditions. Today, the US is enjoying a relatively strong demand environment while coping with the effects of a stronger dollar on exports. Conversely, Japan is deliberately weakening its currency in an effort to kick-start the economy and spur wage inflation. A concentrated portfolio can reflect these trends by focusing only on those US companies exposed to a consumer recovery with solid revenue growth and Japanese exporters that are putting their cash to work for shareholders. This can help create a natural currency hedge – without using derivatives or shorting. And when currencies shift, a concentrated portfolio can take advantage of changing dynamics by tilting a portfolio with a few strategic changes instead of turning over large numbers of holdings. 5. What’s the biggest risk to a concentrated portfolio today? Turmoil in the Chinese markets along with the recent escalation of the Greek debt crisis and the potential for contagion across Europe are, of course, the most significant risks for any global equity manager today. However, we think one of the largest challenges for concentrated allocations today, is how to incorporate downside protection, given the market moves earlier in the year. Defensive segments of global equity markets, such as consumer-staples and income stocks, are expensive. So they may not be as effective in protecting performance during a down market. In concentrated portfolios, where a small number of defensive companies play a vital role in risk management, this could erode the buffers against volatility. Identifying defensive growth companies can help resolve this problem. For example, business services or companies supplying consumer staples have more attractive valuations and can deliver long-term growth – and downside protection, in our view. Similarly, we’d prefer stocks with stable and consistent growth that have attractive policies on returning cash to shareholders as an added feature over pricey stocks that offer income as a primary feature. *Cremers, K.J. Martijn and Petajisto, Antti. “How Active Is Your Fund Manager? A New Measure That Predicts Performance,” March 31, 2009 The views expressed herein do not constitute research, investment advice or trade recommendations and do not necessarily represent the views of all AB portfolio-management teams. AllianceBernstein Limited is authorized and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority in the United Kingdom.