The Low Volatility Anomaly And The Delegated Agency Model

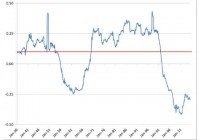

Summary This series offers an expansive look at the Low Volatility Anomaly, or why lower risk stocks have historically produced stronger risk-adjusted returns than higher risk stocks or the broader market. This article hypothesizes that the combination of a cognitive bias and an issue around market structure could contribute to the Low Volatility Anomaly. This article covers a deviation between model and market that may contribute to the outperformance of low volatility strategies. In the last article in this series , I demonstrated that the aversion of certain classes of investors to employing leverage flattens the expected risk-return relationship as leverage-constrained investors bid up the price of risky assets. In addition to the inability to access leverage for long-only investors, the typical model of benchmarking an institutional investor to a fixed benchmark (i.e. the S&P 500 represented through SPY ) could also potentially produce a friction to exploiting the mispricing of low volatility assets (represented through SPLV ). If a security with a beta of 0.75 produces the same tracking error as a security with a beta of 1.25, investors may be more willing to invest in the higher beta security with the belief that it is more likely to generate higher expected returns per unit of tracking error. In this framework, if the investor believes that the higher beta security is going to deliver 2% of alpha and that the higher and lower beta assets are going to have the same tracking error relative to the index, then the investor would not purchase the lower beta asset unless it was expected to earn alpha of more than 2%. An undervalued low beta stock with a positive expected alpha, but an alpha below the expected alpha of a higher beta stock with an equivalent expected tracking error, would be a candidate to be underweight in this framework despite offering both higher expected return and lower expected risk than the broad market. This investor preference results in upward price pressure on higher beta securities and downward price pressure on lower-beta securities that could be a factor in the lower realized risk-adjusted returns of higher beta cohorts depicted in the introductory article in this series . In a foreshadowing of the next article on the potential influence that cognitive biases have on shaping the relationship between risk and return, the difference between absolute wealth and relative wealth could be an important distinction that influences the behavior of delegated investment managers. Richard Easterlin (1974) found that self-reported happiness of individuals varied with income at a point in time, but that average well-being tended to be very stable over long time intervals despite per capita income growth. The author argued that these patterns were consistent with well-being depending more closely on relative income than absolute income. This preference for relative outperformance rather than absolute outperformance may signal why some managers think of risk in terms of tracking error rather than absolute volatility. In perhaps a more salient example, Robert Frank (2011) illustrated the relative utility effect through an experiment that showed that the majority of people would rather earn $100,000 when peers were earning $90,000 than earn $110,000 when peers were earning $200,000. Among the assumptions underpinning CAPM is that investors maximize their personal expected utility, but these studies suggest that investors in effect seek to maximize relative and not absolute wealth. Similar to leverage aversion detailed in the last article, the preference for relative utility could be another CAPM violation that contributes to the Low Volatility Anomaly. Gauging performance versus a benchmark is a form of maximizing relative utility, and has become an institutionalized part of the investment management industry perhaps to the detriment of the desire to capture the available alpha in our low beta asset example. I am not trying to minimize tracking error in my personal account, I am trying to generate risk-adjusted returns to grow wealth over time. As I have demonstrated in this series, academic research has shown that low volatility stocks have outperformed on a risk-adjusted basis since the 1930s. Disclaimer My articles may contain statements and projections that are forward-looking in nature, and therefore inherently subject to numerous risks, uncertainties and assumptions. While my articles focus on generating long-term risk-adjusted returns, investment decisions necessarily involve the risk of loss of principal. Individual investor circumstances vary significantly, and information gleaned from my articles should be applied to your own unique investment situation, objectives, risk tolerance, and investment horizon. Disclosure: I am/we are long SPLV, SPY. (More…) I wrote this article myself, and it expresses my own opinions. I am not receiving compensation for it (other than from Seeking Alpha). I have no business relationship with any company whose stock is mentioned in this article.