The ‘Efficiency’ Of The Market Doesn’t Matter To Smart Investors

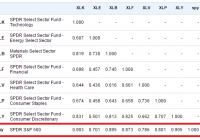

The huge growth in index funds has caused some investors to debate the merits of the market’s “efficiency” and whether index funds would make the markets less efficient. The basic thinking is that if everyone starts buying index funds then that could create more opportunities for stock pickers who are able to go against the grain and pick the stocks that have been unjustifiably correlated to the actions of the overall index. This whole debate confuses why correlations are rising in the first place. Correlations aren’t rising because index funds are becoming more prevalent. Index funds are becoming more prevalent because the performance of the economy is becoming increasingly correlated. If you look at any sector of the S&P 500, you’ll find rising correlations over the course of the last 50 years. The average 10-year correlation of all the sectors of the S&P 500 is about 83.5%: (10-Year Correlation of various sectors) This isn’t happening because index funds are becoming more popular. It’s happening because US corporations are becoming increasingly interconnected. Public companies are becoming multi-national and multi-industry companies whose performance depends increasingly on the way the macroeconomy works. If we look at the underlying Earnings Per Share of these same industries, we find equally strong correlations in their profit growth over time. Of course, high correlations doesn’t mean there won’t be uncorrelated entities whose prices get irrationally whipsawed by the aggregate market performance. But it does mean that it is becoming increasingly difficult to find entities who aren’t dependent on the performance of the broader economy. Finding truly uncorrelated companies is not as easy today as it might have been back in the early 1900s when the broader economy was much more fragmented. Paul Samuelson always argued that the markets were micro efficient, but not macro efficient. Indeed, the whole concept of market “efficiency” is becoming increasingly irrelevant in a world where entire economies are becoming so highly correlated. But this doesn’t change the importance of understanding the discussion and its impact. At the aggregate level, we have all become “asset pickers.” The distinction between “active” and “passive” investors is largely irrelevant in a world where we all now pick baskets of assets inside the global aggregate. And when one deviates from global cap weighting (roughly the Global Financial Asset Portfolio) you are engaging in a form of asset picking that makes you no different than a stock picker. You are declaring that you can generate a better risk adjusted return than the global aggregate. Indexing has become the new stock picking. Instead of picking 25 stocks in an index, we now pick baskets of index funds inside a global aggregate. The idea of “market efficiency” was never very useful to begin with however because it is constructed around a gigantic political strawman. The EMH is essentially a political construct that argues that discretionary intervention is useless because “the market” is smarter than everyone else. It is a political argument against discretionary intervention that was constructed to create a theory of finance that was consistent with an anti government economic theory (Monetarism primarily). In essence, you can’t “beat the market” because the market is so smart. This is silly though. The market will generate the aggregate market return and your real, real return will be the market return minus the rate of inflation, taxes and fees. Taxes and fees alone will reduce the aggregate return by over 35% (if we assume a 10% aggregate return, 1% fees and 25% tax rate). No one will consistently beat “the market” aside from a few lucky outliers. The math just doesn’t work. And the index we are comparing ourselves to is a completely fictitious benchmark because the average real, real return is lower than the pre-tax and pre-fee benchmark to begin with. But the EMH defenders have misconstrued this entire debate to promote a political position constructed by anti government economists at the Chicago School of Economics. Imagine, for instance, that, for the purpose of record keeping, at the end of each NBA basketball game, the NBA reduced the average score of 100 points by 25%, and then imagine that the coaches reduced the score by another 10%. What the EMH defenders have done is argued that the score of 100 means that the teams are all terrible because they cannot, on average beat this “benchmark.” There will be outlier teams who sometimes score more than 100 points, but on average these “professional” teams will underperform. EMH defenders have used this strawman to argue that “active” investors are all terrible. It’s a completely useless construct that does nothing more than misconstrue the entire premise of the discussion. Of course, none of this means that high fees and overly active trading are good. After all, when one engages in such activities they only increase the size of the friction, which reduces returns in the first place. But the debate about EMH and “active” vs. “passive” has been blurred by a useless discussion about how “efficient” the market is. The reality is that we are all active investors to some degree. All indexers have to pick their asset allocations and the funds they will use. All indexers time their entry/exit points, their rebalancing points, their “tilts,” etc. The smarter indexer tries to capture much of the broad market gain while reducing their tax and fee burden. But that has nothing to do with whether the market has become “efficient” or whether some degree of “active” management is “smart” or “stupid.” Samuelson was right – the market is micro efficient and macro inefficient. And as the market has become increasingly macro oriented the discussion about the “efficiency” of the market has become increasingly useless.