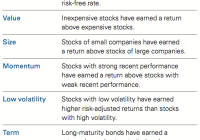

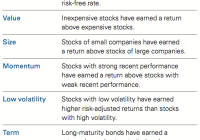

Summary Though factor-based investing has garnered heightened attention recently, related concepts have existed for decades. Factor-based investing potentially offers transparency and control over risk exposures in a cost-effective manner. Factor-based investing is a framework that integrates factor-exposure decisions into the portfolio construction process. By Scott N. Pappas, CFA; Joel M. Dickson, Ph.D. In this paper, we review, discuss, and analyze factor-based investing, drawing the following conclusions: Factor-based investing can approximate, and in some cases replicate, the risk exposures of a range of active investments, including manager- and index-based strategies. Factor-based investing can be used to actively position investment portfolios that seek to achieve specific risk and return objectives. Factor-based investing potentially offers transparency and control over risk exposures in a cost effective manner. A factor-based investing framework integrates factor-exposure decisions into the portfolio construction process. The framework involves identifying factors and determining an appropriate allocation to the identified factors. But what are factors? Factors are the underlying exposures that explain and influence an investment’s risk.[1] For example, the underlying factor affecting the risk of a broad market-cap-weighted stock portfolio is the market factor, also called equity risk. That is, we can consider market exposure as a factor. In this case, not only does the factor exposure influence the risk of a market-cap portfolio, but it has also earned a return premium relative to a “risk-free” asset (often assumed to be short-term, high-quality sovereign debt). Historically, this premium has been a reward to the investor for bearing the additional risk inherent in the market factor. It’s important to note, however, that not all factor exposures are expected to earn a return premium over the long term. That is, factor exposures can be compensated or uncompensated, a critical distinction in any factor-based investing framework. The market factor, for example, has historically earned a return premium, and the general expectation that this premium will persist is what has encouraged investors to purchase broadly diversified stock portfolios. In contrast, some factor exposures are not compensated. Although a relationship may exist between the variation in an investment’s returns and a particular factor, it does not hold that this risk will be rewarded: The factor may simply reflect an idiosyncratic risk that can be removed through effective diversification. For example, the company-specific risk of a single stock should not have an impact on the performance of an effectively diversified portfolio. Although this paper focuses on historically rewarded factors, or factor premiums, we reemphasize that investors should be aware of the distinction between rewarded and unrewarded factors. Indeed, factor-based investing is premised on the ability to identify factors that will earn a positive premium in the future. A large range of factors have been analyzed and debated in the academic literature, and many of these have been used by investors. Figure 1 outlines seven commonly discussed factor exposures that are notable both for the extensive literature documenting each, and for the empirical evidence of historical positive risk-adjusted excess returns associated with them. We do not attempt to exhaustively analyze these factors; rather, we briefly emphasize relevant aspects for investors to consider in evaluating the factor-based approach. Two points should be mentioned at the outset: First, investors may knowingly or unwittingly already hold certain factor exposures within their portfolios. For example, a portfolio of stocks with low price/earnings ratios is likely to have exposure to the “value” factor. Second, the investment case for some factors is subject to ongoing debate- namely, whether past observed excess risk-adjusted returns will continue going forward. Predecessors of factor-based investing Despite the recent interest in factor-based investing, related concepts have existed for decades. For example, value investing, discussed in Graham and Dodd (1934), can be considered a type of factor-based investing. Rather than diversifying across the entire market, value investors focus on a subset of stocks with specific characteristics such as attractive absolute or relative valuations. As this approach gained in popularity, style indexes (both value and growth, for instance) were introduced to better measure the performance of style investors and to provide them with passive vehicles to replicate the returns of active investors. Whether through an index or active management approach, style investing allows portfolios to be created with a style tilt, or, put another way, a factor exposure. Style investments were specifically designed to have return and risk characteristics that differ from those of the broad market. Traditional quantitative-equity investing can also be considered a relative of factor-based investing. Similar to value portfolios, traditional quantitative-equity portfolios are often deliberately allocated to stocks that exhibit certain traits or characteristics. In contrast to style investors, however, traditional quantitative investors generally allocate across a wide range of characteristics-for example, value, momentum, and earnings quality-in an attempt to achieve higher risk-adjusted returns. Traditional quantitative investors may also dynamically adjust allocations in an attempt to generate returns through timing. Again, this approach is based on the belief that portfolios constructed in this way offer risk-and-return characteristics that differ from those of other methods such as indexing. By systematically constructing investment portfolios, factor-based investing uses principles similar to those of both style and traditional quantitative equity investing. In this respect, factor-based investing is simply an evolution of these existing techniques (see Figure 2). Academic research on factor-based investing Academic research related to factor-based investing is extensive (see the “Theory behind factor-based investing”). This paper’s analysis highlights two main areas of special relevance for potential factor investors. The first body of research examines the relationship between factor exposures and returns, specifically the degree to which exposures can explain and influence returns. The second examines the performance of portfolios that allocate to factor exposures. This body of work highlights the theoretical benefits of factor-based investing. Factor exposures and returns As the investment universe has grown beyond stocks and bonds, the drivers of investment returns have become less transparent. Although the relationship between a stock portfolio and the broad market, or a bond portfolio and interest rates, is often clear, it may not be the case for other more complex strategies. Often, it is not immediately obvious what affects the returns of investments such as those in an active portfolio, hedge fund, or alternatively weighted (smart-beta) index. As reported in a number of academic studies, however, factor exposures appear to influence the return of these sometimes complex investments. For example, Bhansali (2011) demonstrated that common factor exposures exist across a diverse range of investments. Research has also shown that the returns of various indexes can be explained by factor exposures. For instance, Amenc, Goltz, and Le Sourd (2009), Jun and Malkiel (2008), and Philips et al. (2011) found that the return on alternatively weighted indexes can be explained by factor exposures. Figure 4 illustrates this point by showing the estimated factor exposures of U.S. equity style categories. The chart shows a strong relationship between factor exposures and style categories. Overall, there is evidence of a relationship between returns and factor exposures across assets, indexes, and style categories. In addition to explaining returns on asset-class investments, research has demonstrated that excess returns generated by active managers can also be related to factor exposures. Bender et al. (2014) provided evidence that up to 80% of the alpha (excess return) generated by active managers can be explained by the factor exposures of their portfolios. Similarly, Bosse, Wimmer, and Philips (2013) demonstrated that factor tilts have been a primary driver of active bond-fund performance. Both studies showed not only that factors play a role in determining the returns of passive investments, but that they also appear to play a critical role in the returns of successful active managers. Portfolios of factor exposures An understanding of factor exposures provides investors with the opportunity to move the focus of the allocation decision from asset classes to factor exposures. The factor-based investing framework thus attempts to identify and allocate to compensated factors-that is, to factors expected to earn a positive return premium over the long term. Research into the factor framework has flourished in recent years and has found that the approach has the potential to improve risk-adjusted returns when used in conjunction with a range of investment portfolio configurations. For example, studies have compared the performance of factor portfolios to a traditional 60% U.S. stocks/40% U.S. bonds portfolio (Bender et al., 2010); diversified funds that include global stocks and bonds, emerging markets, and real estate and commodities (Ilmanen and Kizer, 2012); alternative asset portfolios (Bird, Liem, and Thorp, 2013); and portfolios of active managers (Bender, Hammond, and Mok, 2014). This research has demonstrated that, historically, factor-based investing has improved risk-adjusted returns when combined with a range of diverse portfolios. Practical considerations in factor-based investing The academic research discussed in the preceding section has demonstrated the potential benefits of the factor framework. This section adds practical context to those findings by reviewing five issues that we believe can each strongly affect the success of a factor approach. Again, an in-depth discussion of each issue is beyond the scope of this paper; we simply raise the issues as important considerations when evaluating a factor-based framework. The issues are: implementation, selecting a portfolio’s factor exposures, explaining factor returns, future return premiums, and return cyclicality. Implementation Although the academic literature provides high-level insight into the merits of factor-based investing, few studies have addressed practical implementation issues. One issue, portfolio turnover, for example, may affect investment performance, as a result of transaction costs. That is, actual investment performance may differ from reported academic performance, and these differences will vary depending on the specific factor an investor seeks exposure to. For instance, factor-based investments associated with small or illiquid stocks may present capacity and liquidity issues that are unique to those specific factor-based investments. Although it may be difficult to quantify the exact impact of implementation costs, investors should be aware of the potential for investment performance to vary from reported academic performance. How factor exposures are defined may also affect performance. Differences between broad-market index definitions of asset classes are generally small and result in relatively tight return dispersions across the different definitions. In contrast, factor definitions can differ substantially and may exhibit relatively large return dispersions across different definitions of the same factor. Figure 5 compares the ranges of outcomes experienced for different definitions of market-cap-weighted and factor-based investments. The figure shows that although a group of investors may be invested in the same factor, variations in how that factor is defined may result in a wide range of investment outcomes. Factor exposures, whether generated by passive vehicles or active managers, may require a high level of due diligence to ensure that they offer performance consistent with an investor’s objectives. Selecting a portfolio’s factor exposures Various factors have been analyzed in academic and industry research. Unfortunately, there is no definitive list of what is or isn’t a factor. Further complicating the matter is a continuing debate over the definition of compensated and uncompensated factors. For instance, some factors have demonstrated a strong relationship to the volatility of returns, but have not generated excess returns. Other factors have historically produced excess returns, but there is no guidance as to whether these returns will continue into the future. The allocation decision can be as important in factor-based investing as it is in traditional asset allocation. Not only is the choice of factors an important influence on future returns and risk, but so too is the quantity of factors used in a portfolio. Much of the research highlighting the effectiveness of factor-based investing is based on broadly diversified portfolios of factors. Much like asset-class portfolios, factor portfolios rely on the diversification benefits of different return streams-the larger the number of investments with low or uncorrelated returns, the greater the potential diversification benefits.[2] Factor-based investing has been shown to be particularly effective when applied across asset classes. However, it should be noted that factors associated with different asset classes may still exhibit a high level of correlation. Investors evaluating the factor framework should consider their ability to gain exposure to a range of distinct factors and should be aware that diversification benefits may be limited if portfolios are not effectively diversified across those factors. Explaining factor returns Debate continues on the investment rationale supporting certain factor returns. In some cases-for example, the equity market factor-a strong economic rationale exists for an excess return premium. The equity market premium has been deeply researched, and, although there is uncertainty over the future size of the premium, it is widely accepted that over the long term a positive excess return (above the “risk-free” rate) will be associated with the equity market factor. For many other factors, however, both the logic and economics explaining potential return premiums are subject to debate. Figure 6 briefly summarizes the investing rationale supporting our seven sample factors. There are two main schools of thought on the rationale behind factor returns-risk and investor behavior. Briefly, the risk explanation posits that return premiums are simply rewards for bearing risk or uncertainty. This explanation, consistent with rational asset pricing, assumes that investors obtain return premiums as a reward for being exposed to an undiversifiable risk. The unequivocal view of the equity market factor is that it earns investors a premium as a reward for bearing the uncertainty of the value of future cash flows. In contrast, the behavioral argument holds that certain factor returns are caused by investor behavior. That is, investors make systematic errors that result in distinct patterns in investment returns. Systematic errors, for example, have been offered as an explanation for the existence of the momentum effect. Although the return premiums of some factors have been shown to be clearly related to risk, debate over the source of returns for other factors is more contentious. Nonetheless, investors should be aware of the arguments surrounding specific factors, as this may shape whether and how they allocate to these factors. Future return premiums Expected returns are an important consideration for any investment. Although investors may already be familiar with a range of factor exposures and confident that those exposures will generate positive future returns over the long term, the future returns of other factor exposures may not be so clear. Indeed, there is some conjecture over whether the historical returns associated with certain factors will persist in the future. For example, Lo and MacKinlay (1990), Black (1993), and Harvey et al. (2014) contended that the empirical evidence is a result of data-mining. As it stands, the debate is far from settled and continues in academia and industry. As discussed in the preceding subsection, the investment rationale for certain factors is open to debate. If the behavioral explanation holds for a factor, it may indicate a risk that the return premium may disappear if investors recognize their errors and modify their behavior accordingly-thus adding another layer of uncertainty to the future return premium. Investors may also fear that once a factor has been identified in the academic literature, it will be arbitraged away. Van Gelderen and Huij (2014) have argued against this, however, finding evidence that excess returns from factors are sustained even after they are published in the academic literature. Clearly, although investing in general is associated with a great deal of uncertainty, factor-based investing, of its own accord, has additional unique complexities that investors should consider when evaluating expected returns. Return cyclicality Similarly to asset-class returns, factor returns can be highly cyclical, and investors should be aware that individual factors may underperform for extended time periods. Although this risk is not unique to factor-based investing, it highlights the need for a long-term and disciplined perspective when assessing the factor-based investing framework. As we previously noted, empirical research on factors has found evidence that over the long term some factors have earned excess returns. That research has also demonstrated that the same factors can underperform for lengthy periods. A key component in capturing any potential long-term premium is the investor’s ability to stay the course during periods of poor performance. Figure 7 displays the relative performance of the seven sample factors. The figure illustrates the cyclicality of factor performance: No single factor has consistently outperformed the others during the ten-year period studied. In addition, all factors-at some point in time-have experienced both relatively good and poor performance. Again, this underscores how essential it is to take a long-term perspective when evaluating the factor framework. Applications of factor-based investing Having discussed the theory and practice of factor-based investing, we next focus on its application. First, we discuss why factor-based investing is active management. Second, we consider the risk-and-return characteristics of portfolios of factors. Factor-based investing is active management We believe that a market-cap-weighted index is the best starting point for a portfolio construction discussion. Such a portfolio not only represents the consensus views of all investors, but it has a relatively low turnover and high investment capacity. Constructing a portfolio to obtain factor exposures, however, is an active decision. Factor exposures are often built by creating portfolios of assets around a common characteristic-for example, a portfolio of stocks with high dividend yields. More complex factor implementations may also use leverage or short selling. In each case, factor-based investing involves investors making explicit, or, in some cases, implicit, tilts away from broad asset-class representations expressed by market-cap weights. Investors contemplating factor-based investing should consider their tolerance for active risk. Indeed, tolerance for active risk is a key determinant in the extent to which an investor embraces the factor framework. Whatever the configuration, Vanguard views any portfolio that employs a non-cap-weighted scheme as an active portfolio. Achieving risk-and-returns objectives Figure 8 illustrates excess returns and volatility for the seven sample factors for 2000-2014. Factor exposures can be implemented in a number of ways; to reflect this, the figure presents results for both long-only and long/ short implementations of the value, credit, size, and momentum factors. For the market and term factors, the figure shows long-only results exclusively. For the 15-year period, returns and risk have varied across factors. The figure emphasizes that the way in which factor exposures are implemented can result in differences in performance. As shown, the performance of long/short and long-only implementations has varied significantly for the value, momentum, size, and credit factors over the analysis period. As discussed earlier, much of the research examining the effectiveness of factor-based investing has demonstrated its potential to improve diversification. Such a benefit, however, can depend on how the factor exposures are implemented. Figure 9 compares the correlation between the equity factors of momentum, size, and value with the market factor for both long/short and long-only implementations. For the three factors, a large difference was shown between correlations experienced by long/ short and long-only investors. Correlation was higher for the long-only implementations, which maintain large residual exposures to the market factor. The long/short factors, by contrast, remove much of the market-factor exposure through offsetting short positions, consequently reducing the correlation to the market. The potential diversification benefits of a factor can depend greatly on how the factor is implemented in the portfolio and on whether a distinct exposure to the factor can be obtained. Investors may also consider the potential for factors to generate excess returns. Historically, certain factors have achieved returns in excess of the broad market. While we caution against extrapolating past returns into the future, investors may believe that specific factor exposures offer a prospect for outperformance. We view factor-based investing as taking on active risk even if it is achieved through a passive or index construct. Therefore, we reiterate that before seeking outperformance through allocations to factors, investors should consider their tolerance for active risk. Investors who are comfortable accepting active risk, and confident about their expectations for future returns from factors, may find the factor-based investing framework suitable. But, an important note: Investors taking the view that factor-based investing will outperform over the long run must exercise the discipline required to achieve that return objective. That is, during the inevitable periods of underperformance against the market, investors must be willing to maintain investment allocations through rebalancing and continued investment. Potential benefits of factor-based investing A key takeaway from the academic literature is that many assets, indexes, and active investments have underlying exposures to common factors. Not only can investors access factor exposures in a variety of ways, but they may be doing so unintentionally. Investors may thus ask, what is the most efficient way to gain exposure to factors? An explicit focus on factors can be used to efficiently manage portfolio exposures. In particular, factor-based investing offers potential benefits in transparency, control, and cost. Transparency Previously in this paper, we reviewed research showing that factor exposures can explain and influence returns for a range of diverse investments. A portfolio’s factor exposures, however, may not be clearly apparent. Investors may already have a range of factor exposures in their portfolio-either explicitly through deliberate decisions or implicitly as a result of their investment process. It may be obvious, for instance, that a market-cap-weighted equity index offers exposure to the market factor, but for other investments the factor exposures may not be as clear. More opaque investment vehicles may simply offer factor exposures that can be accessed in a more efficient way. Investments that offer a clear methodology and define their factor exposures may be more effective vehicles for investors. By deliberately focusing on factor exposures as part of the portfolio construction process, investors can potentially gain a clearer understanding of the drivers of portfolio returns. Control A portfolio may already have factor exposures implemented through a variety of investments. For example, some fundamentally weighted, or smart-beta, indexes provide a value factor exposure that varies over time. In contrast, an investment that explicitly targets the value factor may provide a more consistent factor exposure. Investors should consider whether they require direct control of their factor exposures. Although a factor exposure that varies over time may be appropriate for some investors, others may want more direct control over their portfolio’s factor exposures. The decision to delegate factor exposures to a manager or an index, or to maintain direct control over factor exposures, is an important one for investors considering a factor-based framework. Cost Factor exposures can be generated through a number of different investments, and each of these vehicles may charge different levels of fees. In some cases, an investor may be paying high fees to obtain factor exposures that could be available to the investor through a more cost-effective vehicle. By allocating directly to a factor, rather than indirectly through another investment vehicle, investors may be able to access factor exposures more cost-effectively. For example, a passive investment in a factor portfolio may be more cost-effective than an investment through a high-cost active manager or a high-cost index. Each of these investments might offer similar return distributions, but the management fees paid may make the direct factor exposure a more cost-effective approach. To the extent investors have access to low-cost, factor-based investments, such a framework may offer a more prudent way to construct a portfolio. Conclusion Vanguard believes that a market-cap-weighted index is the best starting point for portfolio construction. Factor-based investing frameworks actively position portfolios away from market-cap weights. As discussed here, academic research has demonstrated that the returns on a diverse range of active investments can be explained and influenced by common factor exposures. Using factor-based investments, investors may be able to replicate these exposures. Factor-based investing seeks to achieve specific investment risk-and-return outcomes, greater transparency, increased control, and lower costs. When evaluating a factor-based investing framework, investors should consider not only their tolerance for active risk but the investment rationales supporting specific factors, the cyclicality of factor performance, and their own tolerance for these swings in performance. References Amenc, Noel, Felix Goltz, and Veronique Le Sourd, 2009. The Performance of Characteristics-Based Indices. European Financial Management 15: 241-78. Banz, Rolf W., 1981. The Relationship Between Return and Market Value of Common Stocks. Journal of Financial Economics 9: 3-18. Basu, Sanjoy, 1977. Investment Performance of Common Stocks in Relation to Their Price-Earnings Ratios: A Test of the Efficient Market Hypothesis. Journal of Finance 32: 663-82. Bender, Jennifer, Remy Briand, Frank Nielsen, and Dan Stefek, 2010. Portfolio of Risk Premia: A New Approach to Diversification. Journal of Portfolio Management 36: 17-25. Bender, Jennifer, P. Brett Hammond, and William Mok, 2014. Can Alpha Be Captured by Risk Premia? Journal of Portfolio Management 40: 18-29,12. Bhansali, Vineer, 2011. Beyond Risk Parity. Journal of Investing 20: 110,137-47. Bird, Ron, Harry Liem, and Susan Thorp, 2013. The Tortoise and the Hare: Risk Premium Versus Alternative Asset Portfolios. Journal of Portfolio Management 39: 112-22. Black, Fisher, 1993. Beta and Return. Journal of Portfolio Management 20: 8-18. Bosse, Paul M., Brian R. Wimmer, and Christopher B. Philips, 2013. Active Bond-Fund Excess Returns: Is It Alpha . . . or Beta? Valley Forge, Pa.: The Vanguard Group. Carhart, Mark M., 1997. On Persistence in Mutual Fund Performance. Journal of Finance 52, 57-82. Fama, Eugene F., and Kenneth R. French, 1992. The Cross-Section of Expected Stock Returns. Journal of Finance 47: 427-65. Fama, Eugene F., and Kenneth R. French, 1993. Common Risk Factors in the Returns on Stock and Bonds. Journal of Financial Economics 33: 3-56. Graham, Benjamin, and David Dodd, 1934. Security Analysis. New York: McGraw-Hill. Harvey, Campbell R., Yan Liu, and Heqing Zhu, 2014. . . . and the Cross-Section of Expected Returns. Working Paper. Durham, N.C.: Duke University; available at http://papers. ssrn.com/abstract-2249314. Ilmanen, Antti, and Jared Kizer, 2012. The Death of Diversification Has Been Greatly Exaggerated. Journal of Portfolio Management 38: 15-27. Jun, Derek, and Burton G. Malkiel, 2008. New Paradigms in Stock Market Indexing. European Financial Management 14: 118-26. Lintner, John, 1965. The Valuation of Risk Assets and the Selection of Risky Investments in Stock Portfolios and Capital Budgets. Review of Economics and Statistics 47: 13-37. Lo, Andrew W., and A. Craig MacKinlay, 1990. Data-Snooping Biases in Tests of Financial Asset Pricing Models. Review of Financial Studies 3: 431-67. Mossin, Jan, 1966. Equilibrium in a Capital Asset Market. Econometrica 34: 768-83. Philips, Christopher B., Francis M. Kinniry Jr., David J. Walker, and Charles J. Thomas, 2011. A Review of Alternative Approaches to Equity Indexing. Valley Forge, Pa.: The Vanguard Group. Ross, Stephen A., 1976. The Arbitrage Theory of Capital Asset Pricing. Journal of Economic Theory 13: 341-60. Sharpe, William F., 1964. Capital Asset Prices: A Theory of Market Equilibrium Under Conditions of Risk. Journal of Finance 19: 425-42. Treynor, Jack, 1961. Market Value, Time and Risk. Unpublished manuscript, 95-209. Van Gelderen, Eduard, and Joop Huij, 2014. Academic Knowledge Dissemination in the Mutual Fund Industry: Can Mutual Funds Successfully Adopt Factor Investing Strategies? Journal of Portfolio Management 40: 114: 157-67. Footnotes We consider investable factors in this paper. Another perspective would be to consider economic factor exposures-for example, categorizing investments according to their exposure to economic growth or inflation. This is true only to a point. Although we know of no research on the topic, it is likely that the incremental diversification benefits of additional factors would decrease as the number of factor exposures in a portfolio increases. Notes about risk and performance data: Investments are subject to market risk, including the possible loss of the money you invest. Bond funds are subject to the risk that an issuer will fail to make payments on time, and that bond prices will decline because of rising interest rates or negative perceptions of an issuer’s ability to make payments. Diversification does not ensure a profit or protect against a loss in a declining market. Performance data shown represent past performance, which is not a guarantee of future results. Note that hypothetical illustrations are not exact representations of any particular investment, as you cannot invest directly in an index or fund-group average.