Investing In A Multidimensional Market

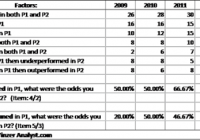

By Bruce I. Jacobs and Kenneth N. Levy, CFA Twenty-six years ago, the Financial Analysts Journal published our findings on the payoffs to stock market “anomalies” – stock price behaviors that were considered anomalous in the context of the efficient market hypothesis. We found the market to be permeated with a complex web of such price behaviors , reflecting the interaction of numerous fundamental and behavioral factors, as well as such institutional features as the regulatory environment. Known anomalies at that time totaled about 25, but no one had considered them jointly. We were the first to recognize the importance of examining multiple anomalies simultaneously. We pioneered the disentangling of the return relationships among numerous anomalies, deriving ” pure ” returns to each one, independent of the influences of all other anomalies. Controlling for cross-correlations among anomalies provides a clearer picture of return-predictor relationships and distinguishes anomalies that are real from those that are merely proxies for other effects. Our findings revealed a much greater dimensionality to the stock market than suggested by the one-factor capital asset pricing model (CAPM) or by previous studies that looked at only one or a few anomalies. A model with greater dimensionality is better able to explain the cross-section of stock returns. Moreover, we have found that the resulting purified returns to anomalies provide better predictions of stock returns than the results from analyzing each anomaly individually. As Harry Markowitz noted in his foreword to Equity Management: Quantitative Analysis for Stock Selection : Such disentangling of multiple equity attributes improves estimates of expected returns. This finding is confirmed in recent empirical work by Lewellen (forthcoming), who showed that using more factors improves the explanatory power of models that aim to predict returns. These findings raise questions about today’s investment trend toward “smart beta” strategies, which target a limited number of anomalies, or factors – such as small size, value, price momentum, and low volatility – that have performed well historically. Smart beta strategies assume a stock market in which a few chosen factors produce persistent returns. As we will discuss, this assumption is not a good approximation of what is observed in reality. The Market’s Multidimensionality Over the last few decades, researchers have uncovered hundreds of factors . But some of these factors can be dismissed because they cannot be replicated or they are unable to predict returns out of sample – either in other time periods or in other markets. The significance of many of the remaining factors may also be questionable. For example, Harvey, Liu, and Zhu argued that many factors have been “discovered” because researchers frequently ignore the possibility that a certain number of factors are bound to show statistically significant results merely by chance. They suggested that given the large number of factors tested to date, using a t -statistic of 3.0, rather than the traditional threshold of 2.0, can help weed out factors that appear valid but are actually only the result of data mining or chance. Even with this more stringent standard, remarkable dimensionality exists in the market. In our original research, we found that 9 of the 25 factors tested were significant, with a t -statistic of 3.0 or higher, when the factor returns were purified via multivariate analysis. Our significant factors included low price-to-earnings ratio, but not low share price; the sales-to-price ratio, but not the book-to-price ratio; earnings surprises within the last month, but not in previous months; relative strength (price momentum); revisions in analysts’ earnings estimates; and return reversals. Small size was marginally significant. (The t -statistic for small size was 2.7. Given the small number of factors that had been tested up to that time, a t -statistic of this magnitude was arguably significant.) Contrary to the CAPM, market beta was not significant even during a bull market. Our list of factors covered most of the factors now included under the smart beta umbrella, and we identified as statistically significant several times the number of factors generally pursued today by smart beta strategies. More recently, Green, Hand, and Zhang confirmed the remarkable multidimensionality of the stock market . They performed multivariate testing on 100 factors and found 24 factors with t -statistics in excess of 3.0. Interestingly, some popular smart beta factors, such as size, book-to-price ratio, and price momentum, were not among the most significant factors. Advantages of a Multidimensional Approach A factor-investing approach that maintains a constant tilt toward one or a few factors is simple and intuitive. However, such an approach ignores potential returns available from other significant factors, as well as the variability over time in returns to the targeted factors. A multidimensional portfolio can achieve exposures to a large number of factors and is thus poised to take advantage of more opportunities than a smart beta strategy that is based on only one or a few factors. Furthermore, a multidimensional portfolio benefits from diversification across numerous factors. It is less susceptible than a smart beta portfolio to the poor performance of any one factor. As some factors underperform, others may outperform, fostering greater consistency of performance. (Because exposure to factors is obtained through holdings in underlying securities, factor diversification in a multidimensional portfolio is achieved through diversified security holdings.) For example, price momentum, a factor used in some smart beta strategies, is prone to occasional crashes. When the market reversed direction after bottoming in 2009, the momentum factor crashed. But returns to the momentum factor tend to be negatively correlated with returns to value factors, because momentum strategies buy past winners and sell losers whereas value strategies typically buy past losers and sell winners. Indeed, when the momentum factor produced large losses in 2009, the book-to-price value factor performed well. To smooth returns, investors may choose to use both a momentum smart beta strategy and a value smart beta strategy. But using separate strategies can be a problem. Although different strategies focus on different factors, their security holdings may overlap, increasing security risk, or the strategies may trade the same security in opposite directions, increasing transaction costs. An alternative is to combine the value factor and the momentum factor in a single portfolio. This approach will also smooth returns while avoiding security overlaps and unnecessary trading. However, such a two-dimensional factor strategy could be improved by using additional factor dimensions. For example, after the market trough in 2009, the small-size factor would have further boosted the performance of the strategy. By combining momentum, value, size, and many other important factors in a multidimensional strategy, it is possible to achieve more consistent performance than can be achieved by a smart beta strategy based on just a few factors. Although returns to factors vary over time (as our previous example highlights), some factors’ return variations may be predictable given the relationships between factors and economic or market conditions. Pure returns to the small-size factor, for instance, may be predictable on the basis of underlying conditions . Because smart beta strategies hold a constant exposure to one or a few factors, regardless of underlying conditions, their performance may be challenged by the variability of factor returns. The rebalancing rules of smart beta strategies also limit their profit opportunities. Consider the returns to earnings surprises and return reversals, which decay quickly. These factors would be difficult to capture with the infrequent rebalancing of most smart beta strategies. Strategies that can trade as opportunities arise are better able to exploit time-sensitive factor returns, provided the trades are expected to be profitable net of transaction costs. Smart beta strategies are often based on common, generic factors used by many managers. This approach leaves their performance susceptible to factor crowding: Too many investors are buying (or selling) the same securities on the basis of the same factors. This can lead to factor overvaluation and factor crises, just as too many investors chasing any asset can lead to overvaluation and corrections. For instance, Khandani and Lo argued that in August 2007, the forced deleveraging of some quantitative hedge funds necessitated their liquidating stocks associated with commonly used factors , which caused performance difficulties for other quantitative managers using similar factors. In addition, the generic nature of the factors used by smart beta strategies, combined with their known rebalancing rules, may render them vulnerable to front running. Front running can occur when traders anticipate the rebalancing needs of smart beta strategies and trade stocks expected to be added to or dropped from smart beta portfolios in the near future. It is well known that the annual rebalancing of the most prominent small-capitalization stock index is affected by front running. Recent evidence has documented adverse price pressure on smart beta strategies that rebalance on the basis of the Fama-French size and book-to-market value factors . As smart beta assets grow, adverse price pressure may increase, leading to higher rebalancing costs. Greater price pressure would create larger opportunities for front runners to profit at the expense of smart beta strategies. Overcrowding and front running are less of a problem for strategies that use proprietary, rather than generic, factors. Proprietary factor definitions are not publicly available and vary from manager to manager, and managers using proprietary factors typically close their strategies to new assets when approaching capacity limits. Because smart beta strategies rely on commonly used factors, they are more likely to encounter price pressures resulting from other managers’ trades or from front runners. The simplicity and transparency of smart beta strategies offer greater accessibility and can result in lower management costs. However, although annual portfolio turnover is usually low for smart beta strategies, trading costs at the periodic rebalancings may be exacerbated by price pressure and front running. Multidimensional strategies, which use numerous factors, are neither simple nor transparent. Hence, assessing the investment process is more demanding for the asset owner. But such strategies can benefit from proprietary factors, which also make them less susceptible to factor crowding and front running. Finally, smart beta strategies shift the decisions about the selection of factors and the timing of factor exposures from the investment manager to the asset owner. In shouldering these responsibilities, asset owners may take on new risks and incur costs beyond the low fees charged by smart beta managers. Multidimensional strategy managers, in contrast, take responsibility for the investment decisions. Conclusion Many years ago, we pioneered the disentangling of a large number of factors in the stock market and showed many to be significant. Subsequent research has confirmed the market’s remarkable multidimensionality: The market has many factors that are both intuitively sensible and statistically and economically significant. We believe that investment strategies based on numerous proprietary factors that dynamically adjust to market conditions have several advantages over smart beta strategies based on a few common, generic factors. Using proprietary factors can provide unique value while mitigating factor crowding and front running. Such a dynamic, multidimensional approach can also improve performance consistency, because it allows for diversification across many proprietary factors and for adjustment of the exposures to those factors over time. Disclaimer: Please note that the content of this site should not be construed as investment advice, nor do the opinions expressed necessarily reflect the views of CFA Institute.