Market Timing Vs. Macro Decision Making

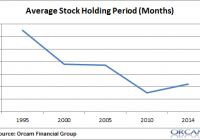

Here’s a very good post over at Brooklyn Investor on some of the differences between market timing and macro hedge funds. As more and more people become index fund investors I think these concepts become increasingly important to understand because all index fund investing is a form of macro investing (picking aggregates). But being an “asset picker” doesn’t make you a “market timer” in the sense that I think many people have come to think. First, market timers are people with extremely short time horizons. These are the people who think they can time the daily, weekly or monthly moves of the market. For some perspective, you can see how much the average holding period has declined over the years: If you go back even further in history the holding period used to be quite a bit longer (as high as 7 years). The crucial point in the discussion about how “active” an investor is really comes down to efficiency in decision making as opposed to “passive” vs “active” (since we’re all “active” to some degree). That is, we all deviate from global cap weighting, we all rebalance, lump sum invest, alter our risk profile, “factor tilt”, etc. Portfolio construction and maintenance is an active endeavor by necessity. The more important questions revolve around how we are optimizing frictions around our decisions. This comes down to two big points: Taxes will take between 15-38% of your profits. Reducing this friction is crucial. A tax aware investor not only uses the proper products to maximize after tax returns, but implements a portfolio that takes advantage of long-term vs short-term capital gains. Fees are the other big friction in a portfolio. As I’ve described before , the difference between using a 1% fee fund and a 0.1% fee fund over the long-term will result in tremendous outperformance: (The fee impact of $100,000 compounded at 7% with avg MF and low fee index) The smart macro investor knows that taxes and fees are a killer in the long-term. If the global financial portfolio generates a return of 7% per year then you can’t afford to be giving away 1% in fees every year and another 1-2%+ to the tax man every year. So here’s a safe rule of thumb – the difference between a “market timer” and someone who makes necessarily “macro decisions” (even if that’s just rebalancing, dollar cost averaging or making new contributions, etc) is 12 months and one day. Since taxes are such a large chunk of our real, real return then it makes sense to take a bit of a longer perspective. Rebalancing on a monthly or quarterly basis doesn’t add much value to your portfolio and increases fees & frictions significantly. At the same time, you have to be careful about the Modern Portfolio Theory concept of “the long-term.” As I described here , taking a “long-term” perspective could actually result in taking much more risk than is appropriate for you. Our financial lives are actually a series of short-terms within one longer time period so it’s best to treat your portfolio as a “savings portfolio” instead of a higher risk “investment portfolio”. As I’ve described in detail , we’re all active investors to some degree. We are all active asset pickers in a world where we all pick asset allocations that deviate from global cap weighting. That’s totally fine! So, the discussion really comes down to how efficient we are at picking our allocations and how we implement the process by which we manage that allocation. If you’re using a very short-term strategy that results in a holding period that is less than 12 months then I’d call you a market timer who is likely increasing your frictions and hurting your overall performance. If, however, you are making macro portfolio decisions in a more cyclical nature (over a year or several years on average) then you are a macro investor who is minimizing the negative impact of portfolio frictions. Of course, the discussion about how to efficiently or effectively we “pick assets” is a whole different discussion and opens up a whole new can of worms in the “active” vs “passive” debate….