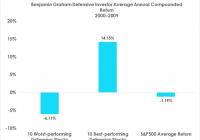

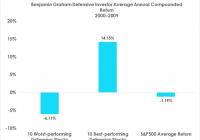

In a previous blog (see Benjamin Graham’s Value Investing versus the Robo-advisor ), I illustrated included a chart outlining the performance of the United States stock market over the course of every decade covering during the past 100 years. Stock performance over the past decade (2000-2009) was not only a net loser, including the paltry dividend income received, but it even underperformed the 1930’s depression era. If the typical investor had known this information at the start of the year 2000, I’m confident he or she would have remained on the sidelines in cash. Let’s assume that Mr. Market held a gun to your head, forcing you to buy and hold stocks over the coming decade. Further assume that you knew the performance in stocks would be terrible. Given few good options against the wrong end of Mr. Market’s gun, one might find some solace by turning to the value investing teachings of Benjamin Graham. How did value stocks perform over the dismal decade from 2000-2009? In Graham’s first edition of The Intelligent Investor , he outlined several approaches to stock selection. One approach was designed for the defensive investor, involving the selection of only stocks that met a conservative set of buying criteria with safety of principal as the primary concern. Another stock selection approach was designed for the more enterprising investor, one willing to assume more risk with the hope of gaining a larger profit. The defensive investor approach to stock selection recommends the following buying criteria: Benjamin Graham’s Stock Selection Rules for the Defensive Investor 1) Diversify your portfolio across at least 10 different securitie s, with a maximum of about 30. Over the decade from 2000-2009, we’ll review the range of portfolio returns for both a “10” and a “30” stock portfolio that met all of Graham’s criteria for the defensive investor. 2) Each company should be large, prominen t, and conservatively financed. We’ll put a company on the defensive investor list only if it had a market cap of at least $350 million. That’s about the size of a larger company in 1949 on an inflation-adjusted basis when Graham published The Intelligent Investor. Graham defined a company as “prominent” if it ranked in the upper-quarter to upper-third in size within a particular industry. We’ll give as many companies the benefit of the doubt as being “prominent” provided they were in the upper-third in size within a particular industry. A “conservatively financed” company according to Graham had total debt under half of its total market capitalization. We’ll screen out all stocks that are leveraged beyond this defensive-investor threshold. 3) Each company should have a long record of continuous dividend payments. The first edition of The Intelligent Investor was published in 1949. Graham was reluctant to exclude companies on the defensive list that discontinued their dividend payments during the 1931-1933 period. After all, that time period occurred shortly after the Dow Jones Industrial Average declined 85% in value, including the dividend income received. Graham must have felt that keeping stocks off of a defensive list simply because the dividend payments were temporarily discontinued during that awful time period was a bit restrictive. As a compromise, Graham allowed all companies to be on the defensive stock list provided that a continuous dividend payment took place on every stock back to the year 1936. That’s a historical 13-year dividend-paying history from the date of Graham’s book publication. We’ll follow a similar approach and require all stocks on our defensive list to have paid an uninterrupted dividend over the previous 13-year period. 4) The price paid for a stock should be reasonable in relation to its average earnings. Graham recommended purchasing only stocks that had a price-to-average-earnings ratio below 20. Average earnings was calculated using the previous five years of data from the income statement of each public company. We’ll follow the same approach and keep off of the defensive list any expensive stocks with a price-to-average-earnings ratio greater than 20. The charts below shows the performance of the best-and worst-performing stocks meeting Graham’s defensive stock criteria covering the worst-performing decade over the past century. The number of stocks at the start of the year 2000 that met all of Graham’s defensive selection criteria totaled 111. Ten Best – and Worst – Performing Defensive Stocks, Including Dividend Income… (click to enlarge) Thirty Best – and Worst – Performing Defensive Stocks, Including Dividend Income… (click to enlarge) As already mentioned, Graham recommended holding between 10 and 30 stocks that met the rigorous defensive stock criteria. As shown in the two charts above, quite a bit of variation in performance existed depending on what stocks were chosen from the defensive list. Diversifying across 30 defensive stocks instead of only 10 improved your worst-case portfolio return over the dismal decade, but it also reduced your potential best-case return. In general, following Graham’s value investing instruction of purchasing a number of defensive stocks stood a good chance of outperforming the broad stock market average over the course of the worst decade in history. Benjamin Graham’s Stock Selection Rules for the Enterprising Investor Graham outlined four broad categories available for the enterprising investor. 1) Buying in low markets and selling in high markets. 2) Buying carefully chosen “growth stocks” 3) Buying bargain issues of various types 4) Buying into “special situations” Choices one and two from the list are highly problematic to implement in real time. Many analysts on Wall Street have attempted to forecast the overall movement of the stock market or the future earnings of a particular company, with mixed results. Option four is a technical branch of investment, and according to Graham, “…only a small percentage of our enterprising investors are likely to engage in it.” We’ll put the microscope over choice number three on the list and look at the performance of buying only bargain issues over the past decade when stock returns scraped the bottom of the barrel. Graham’s bargain approach to stock selection involved either purchasing a stock that traded at a price below some multiple of estimated earnings or selecting securities priced below net current asset value . In a previous blog, we showed how difficult it was to estimate future earnings (see ” Does Earnings Growth Matter When it Comes to Stocks Trading below Liquidation Value? “). Given the challenges of forecasting company earnings, we’ll limit ourselves to only selecting stocks for the enterprising investor list that traded below net current asset value. Stocks that made it on to the enterprising investor list were purchased at a market price below 75% of net current asset value. No more than a 5% weighting was allocated to any one stock. If few stocks could be found meeting our rigorous value criterion, the balance of cash remained in U.S. Treasury Bills. The chart below compares the performance results of Graham’s enterprising investor approach to stock selection with the defensive approach over the dismal decade (2000-2009). Annual rebalancing took place once at the beginning of every yea r, and the capital gains taxes was assumed to be zero. Armed with the knowledge that equity performance over the previous decade (2000-2009) was horrible, you might think a defensive investor had the upper hand over an enterprising investor. In an environment hostile towards stock investing, one might assume that being as conservative as possible would be the better route to take. As illustrated in the chart below, the results are counterintuitive. (click to enlarge) Over the course of the dismal decade, bargain issues using the enterprising approach toward stock selection outperformed defensive stocks by a wide margin. Even if an investor managed to select the top-performing 10-30 stocks that met Graham’s defensive criteria, the portfolio still wouldn’t have outperformed a portfolio of stocks purchased below net current asset value. Negative-return years were more prevalent for the enterprising value investor, but not by much. Aggressive investors endured two negative-return years over the course of the dismal decade, while defensive investors endured only one. A chapter in the book, The Net Current Asset Value Approach to Stock Investing , reviewed the performance over the course of the dismal decade (2000-2009) using a maximum 10% portfolio weighting in any one net current asset value stock rather than the 5% weighting shown in the chart from above. Either way, the average annual return results are about the same and clobber the defensive approach to stock investing. Assuming an investor is willing to stomach greater monthly volatility, it pays to be aggressive even if the overall market provides few value investing opportunities as it did over the course of the period from 2000- 2009 .