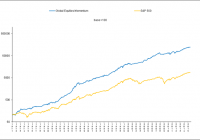

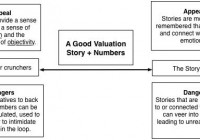

Most people don’t trust DCF valuations, and with good reason. Analysts find ways to hide their bias in their inputs and use complexity to intimidate those who not as well versed in the valuation game. This may surprise you, but I understand and share that mistrust, especially since I know how easy it is to manipulate numbers to yield almost any value that you want, and to delude yourself, in the process. It is for this reason that I have argued that the test of a valuation is not in the inputs or in the modeling, but in the story underlying the numbers and how well that story holds up to scrutiny. Left brain, meet right brain! This fall, as I have twice a year, for almost 30 years, I will be teaching a valuation class at the Stern School of Business at New York University. When the 300 registered students walk into my classroom, I know that they will come in with preconceptions about what the class will cover. Many will bring in their laptops, with the latest version of Microsoft Excel installed, eagerly anticipating session after session on modeling, hoping to become Excel Ninjas, by the time the class is done. They expect it to be a class about numbers, more numbers and still more numbers, with Greek alphabets (alphas and betas) thrown in. I begin the class by asking students to tell me whether each of them is more comfortable with numbers or with stories, and not surprisingly, the class draws disproportionately large numbers of the former, but there are more than a handful of the latter. (There are a number of tests online, like this one , that you can take to make this judgment for yourself, but most of us have a sense without tests.). I then explain my vision of valuation, as a bridge between the two groups, a way of connecting narratives to numbers. While this picture is only an abstraction in that first class, the rest of the class is really my attempt to flesh out the picture and make the bridge real. I don’t always succeed, but my vision of a successful class is that my number crunchers walk out with a little more imagination and that my storytellers acquire a bit more discipline along the way. Connecting Stories to Numbers: The Process The process by which you connect stories to numbers is neither obvious nor intuitive, but it can be learned. In an earlier post on the topic , I laid out five steps in this process, not intended to be either exhaustive or sequential. To illustrate, consider Amazon (NASDAQ: AMZN ), a high profile company where the world is divided into those that believe that it is an extraordinary company with a plan to conquer the world and those that use it as an example of how you can fool a lot of people for a really long time. In a post in October 2014 , I valued Amazon and arrived at a value of $175 per share. (click to enlarge) Rather than get stuck into the details, it is worth laying bare the narrative that I have for Amazon that is determining its value. In my story, Amazon will continue on its path of delivering high revenue growth (with revenues growing to $249 billion by year 10), generally by selling products or offering services at or below cost for the near future (note that margins stay close to zero for the next 5 years), but will eventually start to use its market power to deliver profits, but this market power will be checked by the entry of new players into the retail business, leaving the target margin at a number (7.36%) that reflects the overall retail business in 2014. To see where the optimists in the spectrum come up with higher value, consider an alternative narrative, where Amazon’s market power is unchecked allowing it to expand into more extensively in the media market (with revenues of $329 billion in year 10) and earn an operating margin of 12.84% (the 75th percentile of retail/media firms). Those changes increase the value per share to $468/share. (click to enlarge) To complete the process, consider the pessimistic narrative. In their story, they see Amazon as a company with a charismatic CEO (Jeff Bezos) who is less interested in creating a profitable business than he is in changing the retail world. In that story, Amazon will continue to grow revenues with little attention paid to margins, with the end game being world domination (at least of the retail business). In the valuation, that translates into higher revenue growth and paper-thin operating margins (2.85%, the 25th percentile of large US retail/media firms), even in steady state, the value per share drops to $32/share. (click to enlarge) I followed up my post on narratives and numbers with one on how a change, shift or break in the narrative can translate into a significant change in value , and why the conventional view that intrinsic value, if done right, is timeless is nonsense. Using earnings reports as the vehicles that deliver news about narratives, I looked at my narratives for Apple (NASDAQ: AAPL ), Twitter (NYSE: TWTR ) and Facebook (NASDAQ: FB ) in August 2014, and valued them. Since the last few weeks have brought new earnings reports from all three companies, I will be doing an updated version of that post in the next few days. If you are a number cruncher, this process may seem too free form and subjective to you, and if you are a storyteller, the numbers will seem made up. To me, though, it is the essence of valuation and if you are interested in my extended discussion of this process of connecting narratives to numbers, you may want to take a look at this keynote talk that I gave at the CFA Institute Conference last year. I have to warn you that the length of the webcast (almost 3 hours) could lead you to seek the protection of the Geneva Conventions. Tie to the life cycle: The Investor Angle While narrative and numbers are tied together in every company’s valuation, the importance of each in driving value will shift over a company’s life cycle, as it evolves from a start up to a mature firm to one in decline. Very early in the life cycle, when numbers on the company are either scarce or uninformative, it is almost entirely narrative that drives value. In addition, that narrative can also have a much wider range of possibilities and end values, depending on the path that you map out for the company. In December 2014, I let readers pick their narrative for Uber and mapped out widely divergent values (ranging from less than $1 billion to in excess of $90 billion) for the company, based on the narrative path picked. As companies mature, the numbers start to get weighted more, as it becomes more difficult for companies to not only break away from the past, but the pathways narrow. If you are valuing Coca-Cola (NYSE: KO ), for instance, it is more difficult to visualize explosive breakaways (either up or down in the narrative), though not impossible. If you are an investor uninterested in valuing companies, there are still lessons that you can draw from the link between where a company is in its life cycle and the importance of narrative/numbers. Value Differences: If you get big differences in the perceived value of a young company, they come from fundamentally different narratives about the company, not disagreements about the numbers. Thus, if your assessment of Etsy’s (NASDAQ: ETSY ) value is very different from mine, it is not because we disagree about revenue growth next year but because we have fundamentally different narratives about the company. Value focus: Early in the life cycle, large value changes have to come from large narrative shifts (resulting in large changes in value). Consequently, the focus when you scrutinize earnings reports and other news announcements should be on whether they change your narrative, not on whether the company met or beat some metric (earnings per share, revenues, number of users). To illustrate, much as I have taken issue with the market pricing of Tesla (NASDAQ: TSLA ), I think it seems to me an overreaction, to knock off 15% of its price because it sold 50,000 cars instead of 55,000 , since I see little change in the narrative for Tesla, as a consequence. In contrast, I do think that Tesla’s announcement of a $5 billion investment in a battery factory is cause for a big narrative change (though I am still trying to figure out in which direction), as it may shift your view of the company for an auto manufacturer to an energy producer. (I know… I know… It is time for another look at Tesla as well, and I will…) Value mistakes: If the essence of investing is finding misvalued companies, it seems to me that the odds of doing so are greater early in a company’s life cycle, where narratives can get mangled or when investors overreact to incremental reports. As the investment world gets flatter (in terms of everyone having access to past numbers), the most successful investors of the next millennium will be those are skilled at creating and fine tuning narratives for young companies or those in transition. Tie to the Life Cycle: Implications for managers The link between narratives and value has implications for those who run businesses and for what defines success for a top manager as companies move through the life cycle. Narrative control: If it is narrative that drives value early in the process, it should come as no surprise that the most successful entrepreneurs are the ones who are best at establishing narratives that are compelling, plausible and potentially profitable. Thus, Tesla is lucky to have Elon Musk as a CEO, and Uber has been fortunate with Travis Kalanick at its helm. Both men have their faults (who does not?), but they are enormously gifted storytellers, who (for the most part) have the discipline to stick with their narratives, even in the face of distractions. Narrative consistency: One characteristic that sets apart top managers at those young growth companies that have succeeded is that they have (a) not changed their narratives substantively and (b) have acted consistently with their narratives. The stand out example for this is Jeff Bezos, who has stuck with his narrative of “revenues now, profits later” story for Amazon, sometimes to the chagrin of analysts, and everything that the company has done and continues to do advances that narrative. Mark Zuckerberg has been almost as impressive in his focus on turning Facebook’s immense user base into profits, albeit over a shorter period, but one reason for Twitter’s travails is that there seems to be no coherent narrative emerging about how the company ultimately plans to make money. Bar Mitzvah Moments: In keeping with the theme of this post, which is that narratives have to be tied to numbers, it is worth emphasizing that even the most compelling and consistent narrative will ultimately fail, if the company cannot deliver the numbers to back it up. It is true that this “day of reckoning”, which I labeled a “bar mitzvah” moment , may come later for some companies than for others, but when it does come, you need a management team that recognizes that the market has shifted its focus from narrative to numbers, and behaves accordingly. I have tried to capture the change in balance between narrative and numbers, with the management qualities that are most needed at each stage in the picture below: (click to enlarge) As a company makes it move from young start-up to growth company to mature business, the characteristics that make up a good CEO will change as well. One argument for a strong board of directors and shareholder power even at a well-managed young company is that there may well come a time when the top management has to change with the times or be changed. Work on your weak side There is no one path to valuation nirvana, but I think that you need to find a balance between your storytelling and your number crunching skills, for your valuations to have heft. This balance may come easier to you than it did to me, since my natural instincts are to go with the numbers, and building my storytelling side has been slow going, at times. With each valuation that I do, I still have to force myself to be explicit about the narrative that I am building my valuation around, even when it seems obvious, and each time I do it, it gets a little easier. If you are a natural storyteller, you will probably find yourself resisting just as strongly to working with numbers, but I believe that you too will find a way to strengthen your weak side. I would like to think that a valuation that is the result of both sides of my brain working together is better than one that emerges out of only my left side, but even if it is not, it is a lot more fun getting there. Blog Posts Narrative and Numbers: Modeling, Story Telling and Investing (June 2014) If you build it (revenues), they (profits) will come: Amazon’s Field of Dreams (October 2014) Reacting to Earnings Reports: Narrative Adjustments and Value Effects (August 2014) Up, up and away: A Crowd Valuation of Uber (December 2014) Twitter’s Bar Mitzvah: Is social media coming of age? (November 17, 2014) Reacting to Earnings Reports II: Apple, Twitter and Facebook revisited (August 2015) (Still to come) Valuations Amazon Valuation (October 2014) Uber Valuation (December 2014) Other My keynote talk at the CFA Conference in November 2014 DCF Myth Posts Introductory Post: DCF Valuations: Academic Exercise, Sales Pitch or Investor Tool If you have a D(discount rate) and a CF (cash flow), you have a DCF. A DCF is an exercise in modeling & number crunching. You cannot do a DCF when there is too much uncertainty. The most critical input in a DCF is the discount rate and if you don’t believe in modern portfolio theory (or beta), you cannot use a DCF. If most of your value in a DCF comes from the terminal value, there is something wrong with your DCF. A DCF requires too many assumptions and can be manipulated to yield any value you want. A DCF cannot value brand name or other intangibles. A DCF yields a conservative estimate of value. If your DCF value changes significantly over time, there is either something wrong with your valuation. A DCF is an academic exercise.