Taking ETF Trades To The Next Level

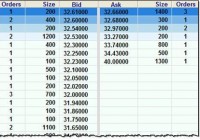

Experienced investors know the theory: ETFs are supposed to trade very close to their net asset value (NAV). And most of the time they do. But this week my PWL Capital colleague Justin Bender and I encountered a glaring exception that could have had expensive consequences. On Monday, Justin and I wanted to sell the iShares U.S. Dividend Growers Index ETF (CUD) in a client’s account. It was a large trade: more than 5,000 shares, which worked out to over $160,000. As we always do before making such a trade, we got a Level 2 quote, which reveals the entire order book. In other words, it tells you how many shares are being offered on the exchange for purchase or sale at various prices. By contrast, a Level 1 quote-the type normally available through discount brokerages-only tells you how many shares are available at the best bid and ask prices. If an ETF’s market maker is doing its job, there should be thousands of shares available at the best price. But we were surprised to find the Level 2 quote looked like this: Source: Thomson ONE Let’s unpack this. As sellers, we looked at the “Bid” column, and the best price (at the top of the column) was $32.61. But we’d be able to sell a mere 200 shares at that price, as revealed in the “Size” column to the left. We could unload another 400 for just a penny less, but after that the prices plummeted. Had we placed a limit order to sell 5,000 shares for $32.60 (one cent below the best bid price), we likely would have seen only 600 shares get sold. But that would have been a minor inconvenience compared to what might have happened if we’d placed a market order. Remember, a market order does not specify a minimum price you’ll accept when selling: it simply tells the exchange you will take whatever is being offered. Assuming a market order for 5,000 shares would have been filled according to the prices above, we would have received as little as $31.65 on the last few hundred shares-almost a full dollar lower than the best bid price. The average price for that market order would have been just $32.23, netting us proceeds of $161,150. Had we been able to sell all 5,000 shares at the best bid price-which is what we’d normally expect-we would have received almost $2,000 more . As you can imagine, we did not place this trade for our client. When market makers take a holiday This lack of depth in an ETF’s order book is very unusual. Even if an ETF is not frequently traded , market makers ensure that thousands of shares are available for purchase or sale at a price very close to NAV. So what was the reason for this anomaly? We can’t be sure, but Justin suspected it was because U.S. markets were closed on Monday (it was Martin Luther King, Jr. Day) while the TSX remained open. CUD is a Canadian-listed ETF, but its underlying holdings are U.S. stocks that were not trading that day: this would have made it more difficult for the market makers to determine the NAV of the fund. Indeed, the lot sizes were so small it’s unlikely they were posted by market makers at all: they may simply have been from individual investors. To test that idea, we got a Level 2 quote for another Canadian ETF that holds U.S. stocks: the Vanguard U.S. Total Market (VUN) . Sure enough, this one showed little market depth as well. Had you tried to sell more than 400 shares (or buy more than about 1,300) you may have seen your order filled at a surprising price. I checked the Level 2 orders for both ETFs again on Tuesday and the situation was completely different. Both funds had 20,000 to 30,000 shares available within a penny of the best bid and ask prices. Lessons learned This was a big trade that most retail investors would never make. But there important lessons from our little adventure that apply to anyone who uses ETFs. First, it’s the most dramatic example I’ve seen for why you should never use market orders . In this situation, a market order would have got you into trouble had you tried to trade as little as $20,000. On a very large trade like ours, it might have been a disaster. Second, avoid trading foreign equity ETFs when the underlying markets are closed. There are several American holidays when the Canadian market remains open, and these are not the days to be making large trades in ETFs that hold U.S. stocks. If you’re making a significant trade in an international equity ETF, it’s also a good idea to pay attention to time zone differences . Finally, if you have a large portfolio, consider subscribing to a service that provides Level 2 quotes. Check with your brokerage to see what is available, because practices vary a lot. Scotia iTRADE provides these free upon request, for example, while RBC Direct Investing and TD Direct Investing offer them as part of their Active Trader programs, and others such as Questrade charge a fee.