Warren Buffett’s Stellar Record In Defying Economic Gravity

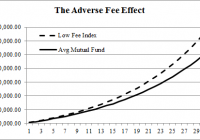

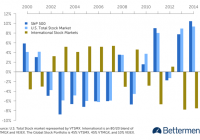

One of the more intriguing observations in Berkshire Hathaway’s new letter to shareholders is Warren Buffett’s reference to what I like to call economic gravity, a.k.a the law of large numbers. There are several ways to keep it at bay (maybe), but in the end it wins no matter what you do. Buffett and company, of course, have an extraordinary history of excelling where so many others have stumbled in this regard. But an unusually long run of success is taking its toll. As Buffett himself recognizes, gravity’s pull is increasing on Berkshire’s prospects. The observation inspires some brief ruminating on how to think about economic gravity generally in the realm of designing and managing investment portfolios. Let’s begin with the salient fact that deserves to precede any discussion of investing that ties in with Buffett, namely: he’s an anomaly in terms of his investment record. That’s something to cheer about if you’ve been a Berkshire shareholder over the last 50 years. But he’s managing expectations down these days: The bad news is that Berkshire’s long-term gains – measured by percentages, not by dollars – cannot be dramatic and will not come close to those achieved in the past 50 years. The numbers have become too big. I think Berkshire will outperform the average American company, but our advantage, if any, won’t be great. Eventually – probably between ten and twenty years from now – Berkshire’s earnings and capital resources will reach a level that will not allow management to intelligently reinvest all of the company’s earnings… Success ultimately plants the seeds of its own destruction… or mediocrity. Buffett, of course, has skirted this curse quite spectacularly through the decades, largely through an uncanny mix of raw talent and steely discipline. A handful of other investors have achieved something similar over long periods of time, but theirs is a tiny club and membership opportunities are limited in the extreme. Accordingly, the overwhelming majority of investment results fall within two standard deviations of the median performance for a relevant benchmark, and that’s not going to change… ever. We’re all fishing in the same pond. The critical differences that separate portfolios (and results) come down to two key factors: asset allocation and rebalancing. Buffett, of course, has opted for a fairly unique asset allocation, as reflected in the companies he’s purchased through the years. The list is a reflection of his talents as an analyst. It’s fair to say that he’s favored a degree of concentration, in large part due to his well-founded confidence in his capabilities to identify value. As for rebalancing, he largely shuns that aspect of portfolio management, which is a direct function of his confidence in security selection. It’s been a winning mix, in large part, due to talent. Concentrated bets with minimal rebalancing has been the basic strategy that’s kept economic gravity to a minimum at Berkshire through time. The results speak for themselves. But gravity- mediocre performance – wins in the end. The best-case scenario is minimizing its bite for a lengthy run, which surely describes Berkshire’s history. For mere mortals in the money game, however, gravity tends to weigh on results much sooner. The reason, of course, is a simple but extraordinarily powerful bit of wisdom attributed to Professor Bill Sharpe a la “The Arithmetic of Active Management” : Properly measured, the average actively managed dollar must underperform the average passively managed dollar, net of costs. There is a finite amount of positive alpha (market-beating performance) and it’s financed exclusively by negative alpha. Buffett’s spectacular achievements over the past 50 years have come at the expense of countless losing investment strategies. But having beaten the grim reaper of financial results for so long, the game is getting harder, as it must. The key point is that mediocrity beckons for every investor… eventually. For some of us (very few of us!) the day of reckoning is far off, due to talent and perhaps even some luck. But for the vast majority of investors (professional and amateur) this is one of those rare instances in money management when the future’s quite clear. This outlook suggests that it may be best to embrace mediocrity from the start via index funds and focus on those aspects of portfolio design and management where the odds look a bit more encouraging for enhancing results a bit. Whereas Buffett favored concentration and minimizing rebalancing, the average investor should do the opposite. In short, hold a multi-asset class portfolio, keep the mix from going to extremes (i.e., periodic rebalancing), and use index funds to keep costs low. It’s the anti-Buffett strategy, which is exactly the wrong strategy if you’re Warren Buffett. Then again, if you wait long enough, perhaps this advice becomes relevant even for the Oracle of Omaha.