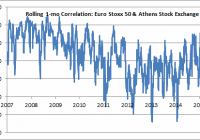

Rising Correlations With Greece In Graphs

Graphical depiction of the correlation between Greek stocks and the rest of the Eurozone. Correlations have been rising as we careen towards a hard deadline on an extension of the current bailout agreement. If a disorderly outcome in Greece unduly drags down stocks in core countries disproportionately, long-term investors should view it as an opportunity. With the Euro-area finance ministers denying Greece a short-term extension of the country’s bailout and with no future financing in place, we are in for a potentially tumultuous week ahead. The Greek government in turn has called for a referendum vote on demands international creditors have made on the country in exchange for ongoing financial aid. Correlations between the exchange between the Euro Stoxx 50 (NYSEARCA: FEZ ) and the Athens Stock Exchange (NYSEARCA: GREK ) have been rising in recent weeks as the ebbing market perception of the likelihood of a deal is felt throughout the continent’s equity markets. Source: Bloomberg As recently as the end of March, the rolling one-month correlation between Greek stocks and a broad gauge of Eurozone stocks was zero. This makes intuitive sense. Greek stocks were subject to increased volatility following the election of the anti-austerity Syriza party in late January. European stocks were rebounding on the back of strengthening European economic data, but Greek stocks were being pulled lower due to the increased uncertainty around its financing package. In recent weeks, Greek stocks and their European counterparts have been seeing heightened correlation as graphed above. If broader European stocks hit an air pocket next week in the face of the Greek referendum vote, broader European stocks could be pulled down unduly in sympathy amidst this heightened correlation. The median company in the Euro Stoxx 50 has a market capitalization six times larger than bottler Coca-Cola Hellenic, the largest company in Athens Stock Exchange, which represents nearly one-fifth of that index. European stocks are being led by the nose by an economy that makes up less than two-percent of its economic output. As I wrote following my recent trip to Greece , if there is a disorderly outcome, the European financial system should be much better equipped given stronger capital ratios, new stability mechanisms, the deployment of quantitative easing, and lower sovereign yields in the periphery. Near-term dislocations due to outsized correlations with Greek stocks and that of the rest of Europe should be viewed as a longer-term opportunity to grab exposure to developed markets that have lagged the performance of the United States post-crisis and could potentially deliver higher forward returns . Disclaimer : My articles may contain statements and projections that are forward-looking in nature, and therefore inherently subject to numerous risks, uncertainties and assumptions. While my articles focus on generating long-term risk-adjusted returns, investment decisions necessarily involve the risk of loss of principal. Individual investor circumstances vary significantly, and information gleaned from my articles should be applied to your own unique investment situation, objectives, risk tolerance, and investment horizon. Disclosure: I/we have no positions in any stocks mentioned, and no plans to initiate any positions within the next 72 hours. (More…) I wrote this article myself, and it expresses my own opinions. I am not receiving compensation for it (other than from Seeking Alpha). I have no business relationship with any company whose stock is mentioned in this article.