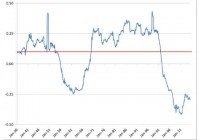

This series digs deeper into the Low Volatility Anomaly, or why lower risk stocks have historically produced stronger risk-adjusted returns than higher risk stocks or the broader market. The CAPM links expected returns with an asset’s sensitivity to systematic risk, but the model assumptions are impractical. This article covers a deviation between model and market that may contribute to the outperformance of low volatility strategies. Given the long-run structural alpha generated by low volatility strategies, I am dedicating a more detailed discussion of the efficacy of this style of investing. In the first article in this series , I provided an introduction to the strategy with a simple example demonstrating a low volatility factor tilt (replicated through SPLV ) from the S&P 500 (NYSEARCA: SPY ) that has generated long-run alpha. In the second article in this series , I provided a theoretical underpinning for the presence and persistence of a Low Volatility Anomaly, and linked to articles depicting its success dating back to the 1930s. This article demonstrates that violations of the assumption of the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM) lead to deviations between model and market that pervert the presumed relationship between risk and return. Empirical evidence, academic research and long time series studies across asset classes and geographies have shown that the actual relationship between risk and return is flatter than the model or market expectations suggests. The third article in this theory lays out a hypothesis for why low volatility strategies have produced higher risk-adjusted returns over time. Leverage Aversion Hypothesis The fallacy of the Capital Asset Pricing Model assumption that investors are able to borrow and lend at the risk-free rate might be the supposition that most perverts the model application from real world practice. Certainly not all investors are able to use leverage, and the cost and availability of leverage can deviate materially from any notion of a risk-free rate in times of stress. Intuitively, leverage-constrained or leverage-averse investors often choose to overweight riskier assets, increasing the price of risky assets and lowering expected return. If some market participants are overweight riskier assets characterized by lower expected returns, then they must be underweight lower risk assets which would be characterized by higher expected returns. In the CAPM model, rational market participants seeking to maximize their economic utility invest in the portfolio with the highest expected return per unit of risk, and lever or de-lever their portfolio to suit their own risk tolerance. In practice, however, many large institutional investors including most mutual funds and certain pension funds are constrained by the level of leverage that they can take. Furthermore, many individual investors lack the sophistication or access to attractively priced leverage. The growing increase in the assets under management of exchange traded fund products with embedded leverage could well signal small investor’s inability to access leverage directly on favorable terms. If market participants respond by being overweight riskier securities, then the relationship between risk and expected return is altered. Building on the long time series studies from Black and Haugen of the relative outperformance of lower volatility assets in the last article in this series, Frazzini and Pederson (2010) empirically demonstrated the alpha-generative nature of low beta assets across twenty international equity markets, Treasury bonds, corporate bonds, and futures. The duo also introduced a “Betting Against Beta” factor that gave the paper its name. The factor is effectively a zero beta portfolio that is long leveraged low-beta assets and short high-beta assets to produce statistically significant risk-adjusted across many markets, geographies, and time intervals. This study also demonstrated that the return of the BAB factor is sensitive to funding constraints as one would expected in a trade involving leverage. The persistence of an alpha-generative strategy involving leverage applied to low volatility assets, whose excess return is in part a function of the funding environment, supports the Leverage Aversion Hypothesis as an explanation for the Low Volatility Anomaly. In the next section of this series, we will tackle how the delegated agency model typical of investment management may also contribute to the outperformance of Low Volatility strategies. Disclaimer My articles may contain statements and projections that are forward-looking in nature, and therefore, inherently subject to numerous risks, uncertainties and assumptions. While my articles focus on generating long-term risk-adjusted returns, investment decisions necessarily involve the risk of loss of principal. Individual investor circumstances vary significantly, and information gleaned from my articles should be applied to your own unique investment situation, objectives, risk tolerance, and investment horizon. Disclosure: I am/we are long SPLV, SPY. (More…) I wrote this article myself, and it expresses my own opinions. I am not receiving compensation for it (other than from Seeking Alpha). I have no business relationship with any company whose stock is mentioned in this article.