Smarter Than Smart Beta?

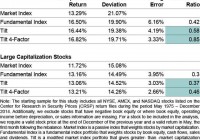

Summary Fundamental Indexation, one popular “smart beta” equity strategy, handsomely outperformed a market-weighted index during the 40 years to December 2014. There is a very pronounced tilt to value in Fundamental Indexation, which weights stocks according to accounting fundamentals rather than by market capitalization. We find that combining market price-based information with fundamental information in a quantitative multi-factor portfolio produces better risk-adjusted performance than either the market or fundamental index. Smarter than Smart Beta? In recent years, smart beta has entered the lexicon of the mutual fund industry and is used to describe certain quantitative investment strategies that aim to beat passive indexes. One of the most popular smart beta strategies is called fundamental indexation. We recently conducted a comprehensive examination of a fundamental indexation strategy using the last 40 years of data and compared this approach to that of two alternative quantitative approaches. The results from the study were revealing. Key findings are outlined below. Fundamentals and Value So what is fundamental indexation? Whereas a traditional passive index such as the Russell 1000 weights stocks by market capitalization, a fundamentals-based index weights stocks according to their accounting fundamentals. So for example, in a market-cap based system, if Apple accounts for 4% of the market cap of the Russell 1000 Index, then it will be assigned a 4% weight. Then, the manager of a fundamental index will increase or decrease Apple’s weight in his index depending on information drawn from Apple’s balance sheet, income statement and statement of cash flows relative to the same accounting information for the other Russell 1000 companies. Proponents of fundamental indexation argue that market-cap weighting will tend to inherently favor high-priced stocks (recall the effects on market-weighted indexes of the tech bubble of the late 1990s) and discriminate against stocks that might be temporarily undervalued. Indeed, the fundamental indexes we constructed in our study for both small cap and large cap stocks handily outperformed their benchmark market indexes during the 40-year period, with lower volatility than the indexes (see “Fundamental Index” in Exhibit 1 below). For this study we assigned index weights, tilting to high fundamentals-to-price stocks (e.g., high book value-to-price), based on the same four accounting factors typically used by fundamental indexers: book equity, along with five-year averages of revenues, operating income before depreciation, and dividends. When we decompose our fundamental indexes, not surprisingly we find a pronounced tilt to value compared to their market cap-oriented indexes, which (given the historical premium for investing in value stocks) helps to explain the excess returns. (click to enlarge) Listening to the Market So far, so good. Now let’s move on to our two alternative approaches, both of which incorporate not only fundamental information but also valuation- or price-based information from the market. In our mind, one weakness of relying exclusively on accounting fundamentals is that they’re stale information (i.e., reported with a lag time). Typically a few months out of date, they also ignore prices and expectations in the market (see Exhibit 2). For a specific example of what I’m talking about, consider the case of Lehman Brothers in the fall of 2008. Lehman started the fourth quarter of 2007 with about $20 billion of book value and, even on the eve of bankruptcy in the fall of 2008, still had close to $18 billion of book value. But by this time the firm’s stock price had collapsed as Lehman was consumed in the financial crisis. A smart beta strategy such as fundamental indexation would not only ignore information in the market price but, because it’s focused solely on the fundamental of book value, would actually signal to double down and buy more Lehman stock. (click to enlarge) So in constructing our two alternative portfolios, we start with the market index and then tilt towards stocks with high fundamental-to-price ratios. For the modified market index (“Tilt” in Exhibit 1), we start with the market index then make tilts using price-scaled information (i.e., fundamental divided by price) from the same four fundamentals that we used in the Fundamental Index. Note that the return and volatility figures for Tilt are very similar to those of Fundamental Index, but that the tracking error and information ratios (NYSE: IR ) are much improved, particularly in the case of small caps. For this study, we chose the IR to measure risk-adjusted portfolio performance (the formula is IR= (Portfolio return – Index return)/Tracking Error). Briefly, tracking error measures divergence from the market index, which by definition has a tracking error of zero (a lower tracking error is better). The IR essentially captures how intelligently different the portfolio’s return is relative to the index (the higher the IR, the better). One reason many portfolio managers and analysts look closely at tracking errors and IR comparisons is due to investor behavior-investors typically seek to beat a market index consistently (a skill that eludes most active fund managers), but get scared if returns swing around wildly and differ dramatically from those of the index. Finally, we studied a four-factor model (“Tilt 4-Factor” in Exhibit 1) that incorporates information from the following four firm characteristics: value, profitability, asset growth, and momentum (for a quick review of factor-based investing, please see my most recent column: ” The Factor-Based Story behind Successful Growth Funds “). Note that this approach combines three so-called slow-moving factors (value, or book equity-to-price; profitability; and asset growth, to which we assign a negative tilt) derived from financial statements with the fast-moving factor of momentum, which reflects price changes for stocks over trailing 12-month periods. We find that this approach, with better factor diversification (e.g., signals from momentum as well as value), produces the best risk-adjusted performance of all, with slightly better returns and lower volatility than for the Fundamental Index and dramatically higher information ratios-twice as high in the case of the small cap stock portfolio. To us, this speaks of the allure of quantitative multi-factor investing, wherein a portfolio manager can combine multiple quantitative insights and improve on a market-based index over extended investment periods. If you would like to learn more about the research I have described in this column, I invite you to read our original study: ” Decomposing Fundamental Indexation .” Conclusion We decomposed fundamental indexation, a leading smart beta investing strategy, during a 40-year period. We find that this modified index has a strong value bent and does indeed outperform the market index by several measurements. But we also find that two alternative portfolio strategies that incorporate market price information generate even stronger risk-adjusted performance results. Disclosure: I/we have no positions in any stocks mentioned, and no plans to initiate any positions within the next 72 hours. (More…) I wrote this article myself, and it expresses my own opinions. I am not receiving compensation for it. I have no business relationship with any company whose stock is mentioned in this article.