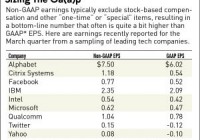

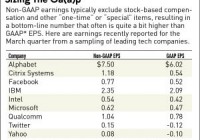

A warning from the chair of the Securities and Exchange Commission is again raising questions about the use of non-GAAP accounting by tech and other publicly traded companies. Skeptics say non-GAAP, or irregular, metrics too often are cherry-picked to make companies look more successful than they are. Worries about not using GAAP (generally accepted accounting principles) seem to rise as more investors and stock pros feel like a bull market has peaked, which is the case now. Non-GAAP metrics were fiercely debated during the super-heated final quarters of the dot-com bubble in 1999 and 2000. The great majority of publicly held tech firms use non-GAAP metrics, as well as SEC-mandated GAAP financials, which serve as a common language for recognizing revenue and expenses. GAAP is supposed to present consistent and reliable financial data to investors, analysts and regulators. It originated in the aftermath of the 1929 market crash and has been updated over the decades, but it’s optimized for old-line industries, such as automobile manufacturing and airlines. It can be less suited for data-centric industries such as social-media and digital-content firms, and that is where non-GAAP has really taken hold. Tech executives like to publish non-GAAP statements because they feel they draw a fuller financial picture of their companies. Often non-GAAP/GAAP strategies are laid right at the start, when privately held companies register for initial public offerings, as executives and private backers strive to get the highest valuation for their business. Non-GAAP Perfectly Legal Under Guidelines Ever cautious about transparency in public financials, the SEC requires, first, that non-GAAP data be accurate. It prohibits executives from putting a greater emphasis on non-GAAP compared to traditional metrics. And regulators insist that non-GAAP guidance be reconciled with GAAP information. Companies often are quite thorough in their earnings releases in explaining what the non-GAAP numbers exclude. Regardless, investors and analysts often focus on the non-GAAP statements, which can be seen as more compelling, and that’s often by design. Executives say the use of non-GAAP accounting is perfectly legitimate. And while many observers agree, some warn that the practice can be abused and can undermine investor confidence. “Forget about the rules for a moment,” Richard Morris, a partner at the law firm Herrick Feinstein, told IBD. Non-GAAP is “telling someone in clear and plain English how you should look at their company,” and that is a valid service. But “without rigorous testing and audits, questionable things get through,” Morris said. “Of course, some of it’s going to be suspect.” CPA Stephen Mannhaupt, a partner-in-charge at accounting firm Grassi & Co., is another guarded proponent. “More clarity is needed,” Mannhaupt said. “The challenge is that unsophisticated investors could be reaching erroneous conclusions about a company’s performance” based on questionable non-GAAP statements. Both he and Morris advocate some extra attention from the SEC. Speaking to the U.S. Chamber of Commerce last month, SEC Chair Mary Jo White said, “we’ve got a lot of concern” about the undisciplined use of non-GAAP metrics. White said she is “really looking at” the matter, including the option of writing new regulation to bring more order to non-GAAP statements. White’s comments can be found at 32:50 in this video . She and the SEC declined to comment for this article. Mannhaupt says White’s goal is worthy. “Companies are really starting to push the envelope. Some (important) costs are not showing up in non-GAAP” guidance, he says, which makes it harder to reconcile GAAP and non-GAAP reporting. Citigroup Takes Aim At Stock Compensation Metric Citigroup surprised many market observers recently, taking aim at a specific non-GAAP metric. Executives say they will not count stock-based compensation the same as a cash expense, a common tactic for sweetening the financials. As a result, Citigroup in early April cut its price targets for shares of some of the biggest Internet companies: LinkedIn.com ( LNKD ), Amazon.com ( AMZN ), Alphabet ( GOOGL ), Facebook ( FB ) and Netflix ( NFLX ). “We are adjusting our models and price targets to better reflect the impact of stock-based compensation (SBC),” Citigroup analyst Mark May said in the research report. “Some may say this is a bear market issue, but we believe it is a necessary change that is long overdue.” It is not hard to see how non-GAAP can obscure financials. There is no obligation for even directly competing businesses to use the same non-GAAP data points. Worse, a widely adopted non-GAAP metric can turn out to be nearly meaningless. One of the more infamous non-GAAP measurements used by Internet companies — which goes back to the dot-com bubble — is eyeballs. Internet entrepreneurs emphasized the number of times people viewed their sites, content and ads. Eyeballs quantified traffic, but traffic alone proved to be a poor indicator of earnings — future or otherwise. For this and many other reasons, dozens of dot-com bubble companies failed. More recently, in 2011, e-commerce marketplace Groupon ( GRPN ) chose not to include some substantial costs in its non-GAAP statements, including the recurring expense of recruiting new members. As a result, according to public-company intelligence firm Audit Analytics, Groupon looked profitable in non-GAAP metrics when it was recording GAAP operating losses. Groupon eventually acceded to the SEC’s demands for greater transparency. Some companies, though, continue their liberal use of non-GAAP accounting. An April 4 research report by investment bank UBS found large differences between GAAP and non-GAAP guidance by companies over the previous 12 months. The report, which sampled 3D printer, storage and computer-hardware firms, found that almost half of the list reported a difference of at least 30% between GAAP earnings per share and non-GAAP earnings per share. UBS declined further comment on its report, and no one contacted for this story would say what they consider to be an acceptable divergence between GAAP and non-GAAP numbers.