The Beginner’s Guide To Volatility: ZIV

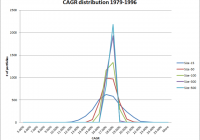

Summary We will cover the basics of ZIV. Examples of trading strategies for the mid-term futures. Current advice on ZIV. Welcome to the final part of The Beginners Guide to Volatility. I highly encourage you to view the two articles below, unless you have already read them. Some terms in this article were previously explained in the first two parts. Part One: The Beginner’s Guide To Volatility: VXX Part Two: The Beginner’s Guide To Volatility: XIV VelocityShares Daily Inverse VIX Medium-Term ETN (NASDAQ: ZIV ) This article will focus on the mid-term VIX futures. To be clear, these products are not the same as the short-term futures products we have discussed before. Some things are similar and others are very different. As a basis for discussion, we will use the inverse product ZIV. I really don’t recommend any other mid-term futures products. What are the mid-term futures? How would an inverse fund operate in the mid-term futures? See below: (click to enlarge) The mid-term futures span months four through seven. An inverse fund, which means in reverse order, sells short month seven’s contract. The fund will hold that contract (short) until selling it when it reaches month four. This process typically takes about 90 days depending on the month and expiration date of the VIX futures. As you may recall from the previous two articles, VIX futures are not the VIX Index and they trade independently of the market and level of stock prices. If you are on vixcentral.com, below the individual months you will see the month seven to four contango box. I have edited this into the above graphic. The first box represents the total percentage of contango or backwardation from month seven to four. For more on these terms, please view the first two articles in this series. The second box represents the estimated amount of contango or backwardation you could expect to profit/loss from during the next 30 days. It takes the first box and divides it by three. Again this is just an estimate. Contango/Backwardation in Mid-Term Futures Charts above and below made by Nathan Buehler using data from The Intelligent Investor Blog . Below, you will see an overlay of ZIV using the same time values to give you a clearer view of the data: Context It is important to view the above chart to put the mid-term futures into context. Although the data is back-tested, it is still relevant and useful. Had you viewed the current data alone (see below), it would appear mid-term future rarely go into backwardation. For the most part, this is true; however, you should be aware of negative economic events that would cause a deeper and more prolonged trek through backwardation. (click to enlarge) Why Consider Inverse Mid-Term Futures? Inverse mid-term futures provide a less volatile bet on decreasing volatility and/or sideways to rising markets. The best reward for your risk would be investing in these products after a dramatic and prolonged spike in the mid-term VIX futures. Historically, investing in mid-term futures now would give you a high risk and minimum reward scenario. See below for an example of a winning strategy: Winning Strategy: Let’s review two strategies that would work well. Buy ZIV once futures re-enter contango from backwardation. Risk of backwardation reappearing. Wait for backwardation and buy ZIV once 5% contango is reached. Visual (click to enlarge) Let’s go over the positives, negatives, and key takeaways with this strategy. Positives: Mid-term futures are already less volatile and less risky than short-term futures. This strategy, especially strategy two, is conservative in managing risk. Negatives: With strategy one, futures could reenter backwardation causing large losses. This opportunity will only occur once a year on average. Some periods may go longer without seeing backwardation present in the mid-term futures. It has been almost four years since the mid-term futures were in backwardation. Takeaways: Your focus on this decision should be in the strength of the U.S. economy and the ever more important global economic impact on the U.S. You need a positive economic outlook and improving or stable economic conditions for this to work as intended. Liquidity One thing you will notice about ZIV in comparison to short-term futures products is the drastically lower volumes. Average volume over the past three months is about 62,000, representing around $2.5-$3 million in transactions per day. As of writing, the fund has $123 million in assets under management (AUM). This represents about 2% of the fund being traded per day. When compared with the ProShares Ultra VIX Short-Term Futures ETF (NYSEARCA: UVXY ) that fund had about $342 million in AUM, and with its near-term average volume of 12 million shares, that represents around $360 million or over 100% of the assets in the fund being traded per day. ZIV will attract investors that are not looking for a day trade and have more of a buy-and-hold or longer-term view of the market. The low volume does not make this an illiquid investment. Conclusion The inverse mid-term VIX futures offer you another way to invest in volatility. It is a much slower pace than the short-term futures but also carries a more moderate level of risk if backwardation persists for a long period of time. Should things turn south, this product is much more forgiving in allowing you to exit a position. Short-term products often react much worse to immediate events. Now is not an opportune time to invest in the mid-term futures, but this article should have given you a good indication of what conditions would look like when the opportunity arises. I appreciate you reading this series, and I hope it continues to serves as a foundational education piece for volatility investors for years to come. My best advice is to fully educate yourself before investing in any VIX-related products. Knowledge is power and very important with this asset class. Disclosure: I/we have no positions in any stocks mentioned, and no plans to initiate any positions within the next 72 hours. (More…) I wrote this article myself, and it expresses my own opinions. I am not receiving compensation for it (other than from Seeking Alpha). I have no business relationship with any company whose stock is mentioned in this article.