Debt Ratios And Pension Ratios: Connecting The Dots Between Them

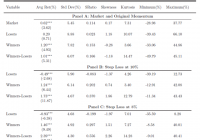

A company with too much debt is like a tall vase with a narrow base. Everything looks fine until you kick the table, at which point it falls over and explodes into thousands of pieces. In an attempt to avoid companies that might explode, I always look for those with “prudent” amounts of debt. At the same time, I try not to be so restrictive that I can’t find anything to invest in. Avoiding companies with too much debt Over the years, I’ve defined “prudent” in several different ways, but my current rules of thumb for interest-bearing debts are: Only invest in a defensive sector company if its Debt Ratio is less than 5 Only invest in a cyclical sector company if its Debt Ratio is less than 4 (doesn’t apply to banks) The Debt Ratio , for reference, is the ratio between the company’s current total borrowings and its 5-year average post-tax profit (preferably normalised or adjusted profits). There is no magic to this; it’s just an approach which I’ve found to be reasonably good at differentiating between companies that are going to run into trouble because of their debts, and those that aren’t (I think I first read it in “Buffettology”, a book I highly recommend). Another financial obligation I’ve kept an eye on for the last few years is defined benefit pension schemes. Many companies don’t have one, but if a company does have one then in most cases (possibly all) it is legally obliged to ensure the pension scheme is well funded. If the pension scheme’s assets do not cover its long-term liabilities, the scheme will have a pension deficit and the company will have a legal obligation to close that deficit at some point. That will often mean shovelling cash into the fund, which means less cash for dividends or other things that create shareholder value. Avoiding companies with excessively large pension obligations I have a rule of thumb for pension obligations as well, just because I like to systemise my decision-making as much as possible. The rule is: Only invest in a company if its Pension Ratio is less than 10 The Pension Ratio is more or less the same as the Debt Ratio, only this time the company’s total defined benefit pension obligations are compared to its 5-year average post-tax profit. So far I’ve always looked at the Debt and Pension Ratios separately; I guess because I never thought about joining the dots, and because I haven’t seen anyone else look at debt and pension liabilities as two sides of the same coin. But last week, when I was reviewing my latest sell decision (June was a “sell” month for me), I noticed that the company in question ( Serco ( OTCPK:SECCF ) ( OTCPK:SECCY ), which I’ll write about soon) had both high levels of debt and a relatively large pension obligation. Specifically, Serco had a Debt Ratio of 5.2, which is too high according to my rules of thumb (Serco is in a cyclical sector and should have, by my rules, a Debt Ratio below 4). That alone would be enough to make me avoid buying the company, although not enough to make me sell it. It also had a Pension Ratio of 8.2, which is okay according to my Pension Ratio rule of thumb, but it’s pretty close to the limit of 10. That got me thinking. What if Serco had a slightly lower Debt Ratio? What if its Debt Ratio was 3.8 and its Pension Ratio was 8.2? That would be “okay” according to my rules of thumb, but is that a sensible outcome? Treating debt and pension obligations as interdependent risks If a company carries interest-bearing debts, then it will need to use cash to pay the interest on those debts. On the other hand, if a company has a large pension obligation then it either has, or could potentially have, a large pension deficit, and that would also require large amounts of cash to clear. Since there is only so much cash to go around, I think it’s sensible to look at these two financial obligations together, rather than in isolation. I don’t have some magical answer that will tell me exactly what a prudent amount of debt is for a company with a particular pension liability, or vice versa. However, I can take a reasonable guess, and refine it from there with experience. So my first stab at a rule of thumb which treats debt and pension obligations as if they impacted one another (because they do) is this: Only invest in a company if the sum of its Debt and Pension Ratios is less than 10 It isn’t rocket science, but I think it’s a good place to start. If, for example, a company has “medium” levels of debt, with a Debt Ratio of perhaps 3, then I would buy it (after a detailed analysis , of course) if its Pension Ratio is below 7. Or, if a company has a pension ratio of 8 then I’ll only buy it if the Debt Ratio is below 2. I think that should give me a fair balance between ruling out companies with excessive obligations, without being so restrictive as to rule out companies that are perfectly capable of handling their current situation. Of course, you may or may not use the same ratios as I do, but even if you don’t, I think treating debt and pension obligations as interdependent risks is still a sensible thing to do.