Scalper1 News

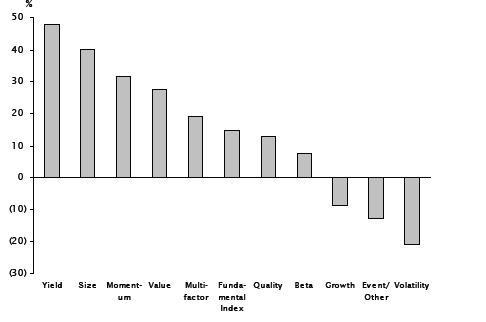

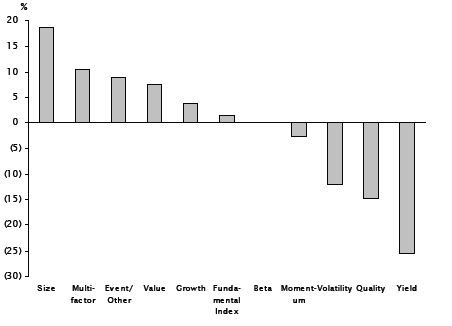

By Kevin Murphy ‘But guns don’t kill people, people do’ is a line less likely to settle an argument than provoke further discussion and yet it is not impossible to imagine an advocate of so-called ‘smart beta’ investments – strategies that try to build on simple index-tracking products by focusing in on a specific factor, such as growth, momentum or value – using a similar refrain. “But smart beta products don’t make bad investment decisions, investors do,” they might tell a doubter. To which we would reply – as we would to anyone trying the gun line – “OK, but they do make the job a lot easier.” We touched on this idea of smart beta products exacerbating investors’ well-documented inability to judge when to buy into and sell out of markets in, among other articles, Smart thinking . That piece was inspired by some fascinating work by our friends at Empirical Research Partners and, since they have recently returned to the subject, we shall too. What Empirical has done is to look at two relationships – first, between past performance and where investors put their money and, second, between where investors put their money and subsequent performance. As you can see from the chart below, for eight out of the 11 categories of smart beta strategies analysed, there is a very strong positive correlation between past performance and future fund flows, with those directing money towards yield-type exchange traded funds (ETFs) apparently the most prone to invest with at least one eye on the rear view mirror. Source: Strategic Insight Simfund, Empirical Research Partners Analysis, June 2015 Here on The Value Perspective, we have no major philosophical issue with investors putting money into areas that have performed well, if – and it is a big if – they continue to perform well. So did Empirical identify any sort of positive relationship between performance in consecutive quarters? Did funds that performed well continue to do so? The answer, as you can see from the following chart, is ‘not really’. Source: Strategic Insight Simfund, Empirical Research Partners Analysis, June 2015 Indeed, returns to yield ETFs are so mean-reverting that, as Empirical observes: “If anything, investors should be buying them after down-quarters rather than up-quarters.” As value investors, we also cannot resist pointing out how momentum ETFs have a negative correlation here too – after all, the one quality investors might think they could count on from such a strategy would be, well, momentum. One final aspect of Empirical’s research we would highlight is the finding that, on average, smart beta strategies turn over about a third of their total capitalisation every month. This would of course imply the average holding period for a smart beta investor is three months – in other words, the average holding period mirrors the time frames of fund flows and performance discussed above. The picture being painted here is of a dispiriting and, to our minds, frankly nonsensical investment routine, where your average smart beta investor sees good performance, buys it, sells up after a quarter of likely disappointing performance, buys something else that has performed well, sells up after a quarter of likely disappointing performance and on and on until, presumably, they have no money left. No doubt, the groups that run smart beta strategies would argue they are intended to allow investors to tilt their exposure to factors they believe will deliver strong performance over the longer term. The reality seems to be, however, that that is not how many people use them – choosing instead to churn smart beta ETFs in the hope of squeezing the best possible performance from quarter to quarter. As we never tire of pointing out here on The Value Perspective, nothing in life is certain but, if anything came close, it would be that such a hope is destined to end in disappointment. Ultimately, one of the supposed selling points of smart beta ETFs – the ease with which investors can pick out and trade a particular strategy – is working against them. Instead of tangible companies, complete with management teams, business models and financial statements, ETF investors are buying into ethereal concepts that are based on other people’s definitions of value or momentum, say – and, if one does not work, it is significantly easier to give up and buy an alternative. That of course is the antithesis of what value investors look to do, preferring instead to play the patient, long-term game, with an average holding period of three or five years. Scalper1 News

By Kevin Murphy ‘But guns don’t kill people, people do’ is a line less likely to settle an argument than provoke further discussion and yet it is not impossible to imagine an advocate of so-called ‘smart beta’ investments – strategies that try to build on simple index-tracking products by focusing in on a specific factor, such as growth, momentum or value – using a similar refrain. “But smart beta products don’t make bad investment decisions, investors do,” they might tell a doubter. To which we would reply – as we would to anyone trying the gun line – “OK, but they do make the job a lot easier.” We touched on this idea of smart beta products exacerbating investors’ well-documented inability to judge when to buy into and sell out of markets in, among other articles, Smart thinking . That piece was inspired by some fascinating work by our friends at Empirical Research Partners and, since they have recently returned to the subject, we shall too. What Empirical has done is to look at two relationships – first, between past performance and where investors put their money and, second, between where investors put their money and subsequent performance. As you can see from the chart below, for eight out of the 11 categories of smart beta strategies analysed, there is a very strong positive correlation between past performance and future fund flows, with those directing money towards yield-type exchange traded funds (ETFs) apparently the most prone to invest with at least one eye on the rear view mirror. Source: Strategic Insight Simfund, Empirical Research Partners Analysis, June 2015 Here on The Value Perspective, we have no major philosophical issue with investors putting money into areas that have performed well, if – and it is a big if – they continue to perform well. So did Empirical identify any sort of positive relationship between performance in consecutive quarters? Did funds that performed well continue to do so? The answer, as you can see from the following chart, is ‘not really’. Source: Strategic Insight Simfund, Empirical Research Partners Analysis, June 2015 Indeed, returns to yield ETFs are so mean-reverting that, as Empirical observes: “If anything, investors should be buying them after down-quarters rather than up-quarters.” As value investors, we also cannot resist pointing out how momentum ETFs have a negative correlation here too – after all, the one quality investors might think they could count on from such a strategy would be, well, momentum. One final aspect of Empirical’s research we would highlight is the finding that, on average, smart beta strategies turn over about a third of their total capitalisation every month. This would of course imply the average holding period for a smart beta investor is three months – in other words, the average holding period mirrors the time frames of fund flows and performance discussed above. The picture being painted here is of a dispiriting and, to our minds, frankly nonsensical investment routine, where your average smart beta investor sees good performance, buys it, sells up after a quarter of likely disappointing performance, buys something else that has performed well, sells up after a quarter of likely disappointing performance and on and on until, presumably, they have no money left. No doubt, the groups that run smart beta strategies would argue they are intended to allow investors to tilt their exposure to factors they believe will deliver strong performance over the longer term. The reality seems to be, however, that that is not how many people use them – choosing instead to churn smart beta ETFs in the hope of squeezing the best possible performance from quarter to quarter. As we never tire of pointing out here on The Value Perspective, nothing in life is certain but, if anything came close, it would be that such a hope is destined to end in disappointment. Ultimately, one of the supposed selling points of smart beta ETFs – the ease with which investors can pick out and trade a particular strategy – is working against them. Instead of tangible companies, complete with management teams, business models and financial statements, ETF investors are buying into ethereal concepts that are based on other people’s definitions of value or momentum, say – and, if one does not work, it is significantly easier to give up and buy an alternative. That of course is the antithesis of what value investors look to do, preferring instead to play the patient, long-term game, with an average holding period of three or five years. Scalper1 News

Scalper1 News