Scalper1 News

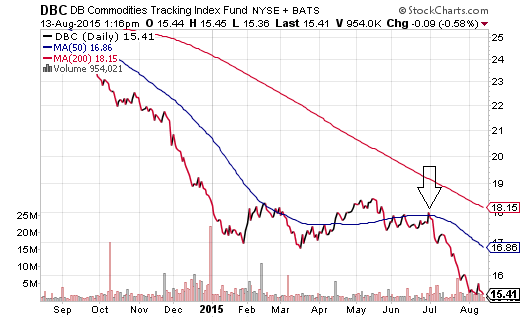

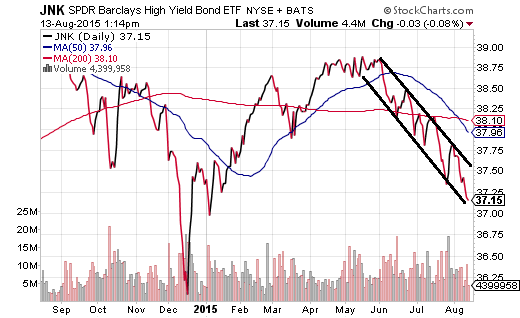

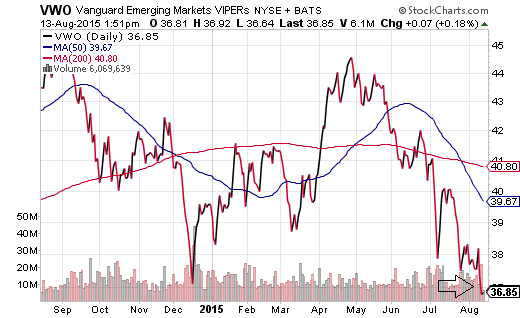

In an effort to boost the U.S. economy, the central bank of the United States has used higher stock prices as a weapon of perceived wealth creation. Here’s the downside. When you implicitly and explicitly suggest that rates will remain lower for longer, people begin to count on risky assets being safer than they are. With all four of the classic canaries unable to serenade, the historical probability of a sharp correction for the broader U.S. market increases significantly. Eleven months ago, I talked about four classic canaries in the investment mines: (1) commodities, (2) high yield bonds, (3) small-cap stocks, (4) emerging market stocks. I explained that when all four of those canaries stop singing, riskier ETFs tend to break down. Indeed, in September of 2014, commodities were tanking, high-yield bonds were plunging, small-cap stocks were faltering and emerging market stocks were plummeting. The canaries were losing their voices. Not surprisingly, the broader U.S. markets eventually followed suit in rather dramatic fashion. In fact, everyone’s favorite large-cap benchmark (S&P 500) had nearly pulled back 10% from a record high. Then came the 16th of October. Stocks had coughed up yet another 1% through mid-day. With the broad-market benchmark pushing the 10% correction level, the president of the St. Louis Fed, James Bullard, suggested that his colleagues at the U.S. Federal Reserve could always rethink the use of additional bond buying with an extension of quantitative easing (QE). And at that time, Bullard talked about worldwide economic uncertainty being a reason for continuing “QE3.” Here’s what happened next: Today, the “Bullard Bounce” still reverberates off the walls and ceilings of the New York Stock Exchange. Why? Investors believe the Fed is willing to do whatever it takes to preserve higher stock prices. Keep in mind, in an effort to boost the U.S. economy, the central bank of the United States has used higher stock prices as a weapon of perceived wealth creation. When you pressure investors to take on risks that they would not normally have taken by pushing interest rates to ‘rarely-before-seen’ lows – and when you entice consumers to finance gratification through credit rather than through savings – asset prices rise precipitously. Higher home prices and higher stock prices make people feel wealthier. Here’s the downside. When you implicitly and explicitly suggest that rates will remain lower for longer, people begin to count on risky assets being safer than they are; similarly, the size of debts can become some so large that those who trusted the policy makers lose the ability to service the debt (let alone pay it back) when borrowing costs go up. Now let us tie together last year’s four classic canaries with the subsequent Bullard bounce and today’s financial markets. The PowerShares DB Commodity Index Tracking ETF (NYSEARCA: DBC ) has accelerated its decline since July and currently seeks depths that haven’t been seen since the heart of the Great Recession. That’s one canary that cannot sing. Meanwhile, high yield bonds via the SPDR Barclays Capital High Yield Bond ETF (NYSEARCA: JNK ) is accelerating its decline that began in June. Canary #2 has a bone its throat. Circumstances are not much better for small-cap stocks and emerging market stocks. The iShares Russell 2000 ETF (NYSEARCA: IWM ) sports a P/E of 20.6 according to Morningstar. It has fallen 6.3% from its late June pinnacle and sits slightly below its long-term 200-day moving average. In another words, Canary Numero 3 is having difficulty vocalizing. The Vanguard FTSE Emerging Markets ETF (NYSEARCA: VWO ) may provide value-du-jour with is P/E of 14, yet China’s recent currency devaluation and Russia’s oil price losses make it difficult for investors to see a forest for the trees. After all, VWO is sitting near 52-week lows and has been in a steep downtrend since May. (The fourth of the four canaries isn’t singing.) With all four of the classic canaries unable to serenade, the historical probability of a sharp correction for the broader U.S. market increases significantly. What’s more, just like the September-October pullback of 2014, market internals have been deteriorating at a noteworthy pace, whether one is looking at waning breadth of bullish stock participation or widening credit spreads between investment grade and higher yielding corporates/junk corporates. It follows that a sell-off not unlike the one that occurred in September-October of 2014 is extremely likely to transpire here in 2015. However, there are several differences this time around. For one thing, revenues have declined for two consecutive quarters, making valuations even more questionable than in 2014. In a similar vein, earnings have gone flat. Historically, stocks tend to fade when corporations are less capable of producing top-line and bottom-line results (as opposed to merely beating the analyst estimates). What’s more, this time around, there’s less certainty of the Federal Reserve defending stocks at the 10% correction level. Granted, Bullard employed a “do whatever it takes” strategy to send stocks skyrocketing last year by bringing up global economic uncertainty. It would be extremely easy for the Fed to use an excuse that economic weakness in Europe, Asia, Australia, Latin America – pretty much everywhere – requires that they tighten at a sloth’s pace. For example, they raise rates at one-eight of a point rather than one-quarter, or they execute a one-n-done quarter-point for 3-6 months. That would likely encourage risk assets to get back on track. Nevertheless, until there is clarity on Fed policy, all of the signs point to “risk-off” outperforming “risk-on.” Downside risks remain elevated until the Federal Reserve shines light on its game plan going forward. Even if the path for tightening is described as ultra-slow and measured, investors will need to weigh just how much the higher costs of borrowing might adversely impact the cost of debt servicing for corporations; that is, we may see further erosion of profitability from an earnings picture that is already flat. People, companies as well as countries tend to forget that debt is still debt. If the overall cost of servicing debt is lowered through rate games, and the debts are increased because families/corporations/nations are taking the worm on the fish hook, it does not mean that the hook itself won’t cause severe damage or death. Again, non-financial corporations are more leveraged at 37% than they were in 2007 at 34%. Higher borrowing costs from the U.S. Federal Reserve? That’s going to be more than an inconvenient challenge. Disclosure: Gary Gordon, MS, CFP is the president of Pacific Park Financial, Inc., a Registered Investment Adviser with the SEC. Gary Gordon, Pacific Park Financial, Inc, and/or its clients may hold positions in the ETFs, mutual funds, and/or any investment asset mentioned above. The commentary does not constitute individualized investment advice. The opinions offered herein are not personalized recommendations to buy, sell or hold securities. At times, issuers of exchange-traded products compensate Pacific Park Financial, Inc. or its subsidiaries for advertising at the ETF Expert web site. ETF Expert content is created independently of any advertising relationships. Scalper1 News

In an effort to boost the U.S. economy, the central bank of the United States has used higher stock prices as a weapon of perceived wealth creation. Here’s the downside. When you implicitly and explicitly suggest that rates will remain lower for longer, people begin to count on risky assets being safer than they are. With all four of the classic canaries unable to serenade, the historical probability of a sharp correction for the broader U.S. market increases significantly. Eleven months ago, I talked about four classic canaries in the investment mines: (1) commodities, (2) high yield bonds, (3) small-cap stocks, (4) emerging market stocks. I explained that when all four of those canaries stop singing, riskier ETFs tend to break down. Indeed, in September of 2014, commodities were tanking, high-yield bonds were plunging, small-cap stocks were faltering and emerging market stocks were plummeting. The canaries were losing their voices. Not surprisingly, the broader U.S. markets eventually followed suit in rather dramatic fashion. In fact, everyone’s favorite large-cap benchmark (S&P 500) had nearly pulled back 10% from a record high. Then came the 16th of October. Stocks had coughed up yet another 1% through mid-day. With the broad-market benchmark pushing the 10% correction level, the president of the St. Louis Fed, James Bullard, suggested that his colleagues at the U.S. Federal Reserve could always rethink the use of additional bond buying with an extension of quantitative easing (QE). And at that time, Bullard talked about worldwide economic uncertainty being a reason for continuing “QE3.” Here’s what happened next: Today, the “Bullard Bounce” still reverberates off the walls and ceilings of the New York Stock Exchange. Why? Investors believe the Fed is willing to do whatever it takes to preserve higher stock prices. Keep in mind, in an effort to boost the U.S. economy, the central bank of the United States has used higher stock prices as a weapon of perceived wealth creation. When you pressure investors to take on risks that they would not normally have taken by pushing interest rates to ‘rarely-before-seen’ lows – and when you entice consumers to finance gratification through credit rather than through savings – asset prices rise precipitously. Higher home prices and higher stock prices make people feel wealthier. Here’s the downside. When you implicitly and explicitly suggest that rates will remain lower for longer, people begin to count on risky assets being safer than they are; similarly, the size of debts can become some so large that those who trusted the policy makers lose the ability to service the debt (let alone pay it back) when borrowing costs go up. Now let us tie together last year’s four classic canaries with the subsequent Bullard bounce and today’s financial markets. The PowerShares DB Commodity Index Tracking ETF (NYSEARCA: DBC ) has accelerated its decline since July and currently seeks depths that haven’t been seen since the heart of the Great Recession. That’s one canary that cannot sing. Meanwhile, high yield bonds via the SPDR Barclays Capital High Yield Bond ETF (NYSEARCA: JNK ) is accelerating its decline that began in June. Canary #2 has a bone its throat. Circumstances are not much better for small-cap stocks and emerging market stocks. The iShares Russell 2000 ETF (NYSEARCA: IWM ) sports a P/E of 20.6 according to Morningstar. It has fallen 6.3% from its late June pinnacle and sits slightly below its long-term 200-day moving average. In another words, Canary Numero 3 is having difficulty vocalizing. The Vanguard FTSE Emerging Markets ETF (NYSEARCA: VWO ) may provide value-du-jour with is P/E of 14, yet China’s recent currency devaluation and Russia’s oil price losses make it difficult for investors to see a forest for the trees. After all, VWO is sitting near 52-week lows and has been in a steep downtrend since May. (The fourth of the four canaries isn’t singing.) With all four of the classic canaries unable to serenade, the historical probability of a sharp correction for the broader U.S. market increases significantly. What’s more, just like the September-October pullback of 2014, market internals have been deteriorating at a noteworthy pace, whether one is looking at waning breadth of bullish stock participation or widening credit spreads between investment grade and higher yielding corporates/junk corporates. It follows that a sell-off not unlike the one that occurred in September-October of 2014 is extremely likely to transpire here in 2015. However, there are several differences this time around. For one thing, revenues have declined for two consecutive quarters, making valuations even more questionable than in 2014. In a similar vein, earnings have gone flat. Historically, stocks tend to fade when corporations are less capable of producing top-line and bottom-line results (as opposed to merely beating the analyst estimates). What’s more, this time around, there’s less certainty of the Federal Reserve defending stocks at the 10% correction level. Granted, Bullard employed a “do whatever it takes” strategy to send stocks skyrocketing last year by bringing up global economic uncertainty. It would be extremely easy for the Fed to use an excuse that economic weakness in Europe, Asia, Australia, Latin America – pretty much everywhere – requires that they tighten at a sloth’s pace. For example, they raise rates at one-eight of a point rather than one-quarter, or they execute a one-n-done quarter-point for 3-6 months. That would likely encourage risk assets to get back on track. Nevertheless, until there is clarity on Fed policy, all of the signs point to “risk-off” outperforming “risk-on.” Downside risks remain elevated until the Federal Reserve shines light on its game plan going forward. Even if the path for tightening is described as ultra-slow and measured, investors will need to weigh just how much the higher costs of borrowing might adversely impact the cost of debt servicing for corporations; that is, we may see further erosion of profitability from an earnings picture that is already flat. People, companies as well as countries tend to forget that debt is still debt. If the overall cost of servicing debt is lowered through rate games, and the debts are increased because families/corporations/nations are taking the worm on the fish hook, it does not mean that the hook itself won’t cause severe damage or death. Again, non-financial corporations are more leveraged at 37% than they were in 2007 at 34%. Higher borrowing costs from the U.S. Federal Reserve? That’s going to be more than an inconvenient challenge. Disclosure: Gary Gordon, MS, CFP is the president of Pacific Park Financial, Inc., a Registered Investment Adviser with the SEC. Gary Gordon, Pacific Park Financial, Inc, and/or its clients may hold positions in the ETFs, mutual funds, and/or any investment asset mentioned above. The commentary does not constitute individualized investment advice. The opinions offered herein are not personalized recommendations to buy, sell or hold securities. At times, issuers of exchange-traded products compensate Pacific Park Financial, Inc. or its subsidiaries for advertising at the ETF Expert web site. ETF Expert content is created independently of any advertising relationships. Scalper1 News

Scalper1 News